Try our favorite, clean protein powder: See our top pick →

Try our favorite, clean protein powder: See our top pick →

Evidence Based Research To fulfill our commitment to bringing our audience accurate and insightful content, our expert writers and medical reviewers rely on carefully curated research.

Read Our Editorial Policy

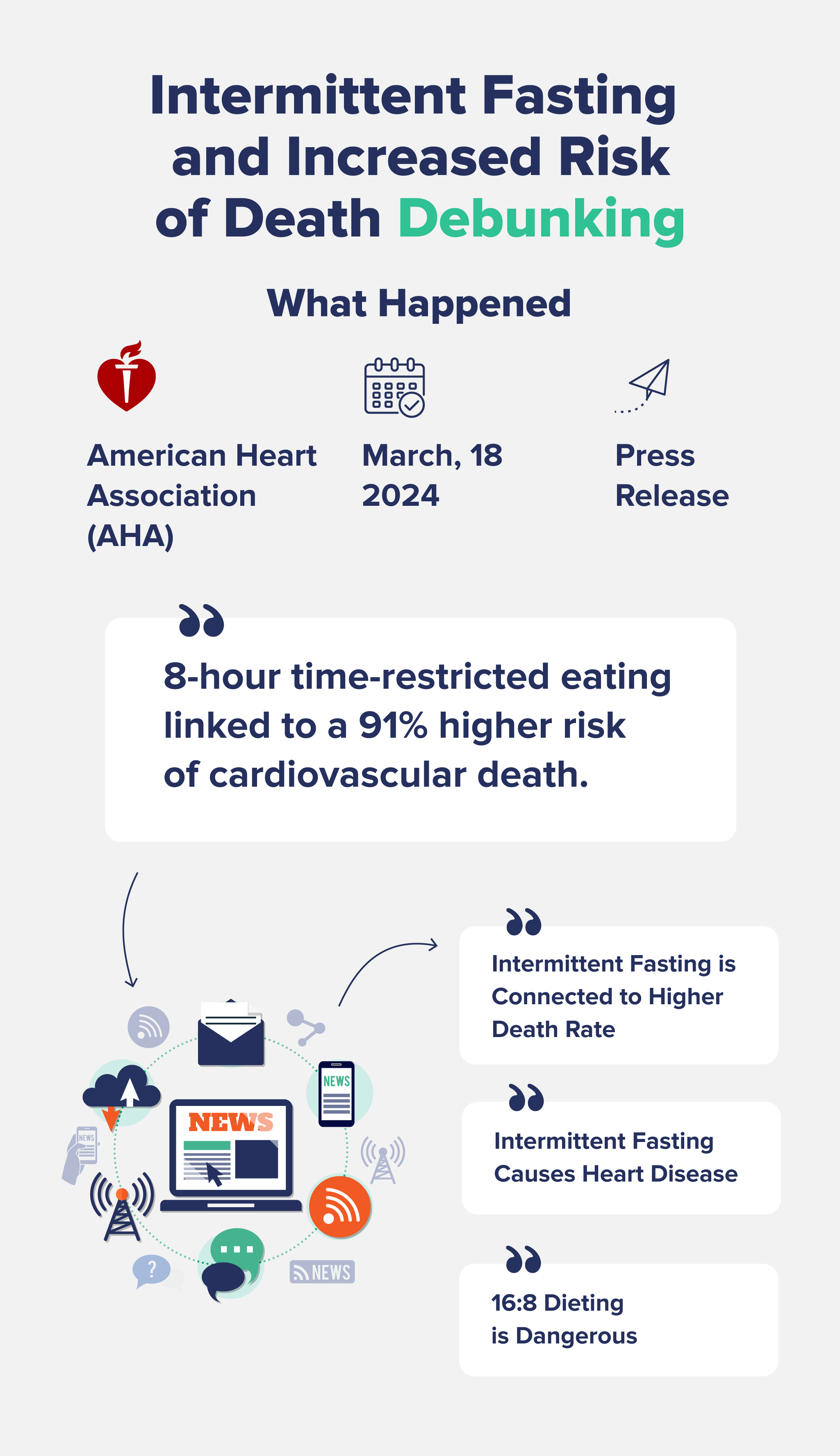

The American Heart Association recently put out a press release in March 2024 claiming that intermittent fasting—specifically a 16:8 fast, or fasting for 16 hours and eating within an 8-hour window—is linked to a 91% increased risk of dying from heart disease.

Yep, you read that right: 91%!

But the headlines aren’t quite what they seem—let’s dive into the details of this research and find out exactly what it’s telling us.

The AHA posted a press release titled “8-hour time-restricted eating linked to a 91% higher risk of cardiovascular death,” and media outlets all over the world have picked it up with various extreme headlines.

This press release was based on an unpublished study by researchers out of Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China, where they looked at dietary surveys from over 20,000 adults with an average age of 49.

The research team found that people who restricted their eating windows to eight hours per day had a 91% increased risk of dying from cardiovascular disease compared to people who followed a more regular eating schedule of 12-16 hours per day.

They also reported that people with existing heart disease who ate in an 8-10 hour window had a 66% higher risk of death from heart disease or stroke.

While that all sounds pretty bad, let’s take a closer look at what this research actually means.

First, this press release was based on a poster presentation at an American Heart Association conference—it has not been peer-reviewed or published yet. While this doesn’t necessarily mean it’s not of sound quality, it just means that other experts in the field have not had a chance to review, challenge, or approve it.

Second, the data came from NHANES surveys, which are based on dietary recalls or food-frequency questionnaires, from 2003 to 2018. Essentially, food-frequency questionnaires ask you to recall a certain food or amount of food that you ate during a specific time period.

As you can imagine, dietary recalls like this are pretty notorious for low accuracy. After all, most people have trouble remembering what they ate for breakfast two days ago, let alone months or years ago.

Third, the research only included data from two days’ worth of dietary recall samples for each participant, including people as “intermittent fasters” if they ate during an 8-hour window just during those two days. As this is not necessarily the criteria for intermittent fasting—it probably means they just skipped breakfast—these two days’ worth of data likely are not an accurate representation of people who fast.

Fourth, we don’t know if these people were intentionally intermittent fasting—which is unlikely, as intermittent fasting was not yet a “thing” for the majority of the study’s time period of 2003 to 2018. We also don’t know if they didn’t eat breakfast for another reason, like high stress, busy jobs, shift work, attempting to lose weight for a health condition, low food security, or medications or illness causing low appetite, for example.

Fifth, the study participants who ate in the 8-hour window were more likely to be male, current smokers, and had higher BMIs, all of which are considered risk factors for heart disease. While these factors were adjusted for in statistical analysis, other cardiovascular risk factors relevant to intermittent fasting—like stress, sleeping patterns, shift work, and nutritional quality of their diet—were not.

Lastly, as is the nature of all observational studies, correlation does not equal causation. This means that intermittent fasting does not cause heart disease—just that, in this particular two-day time period, there was an association between people who didn’t eat breakfast and heart disease mortality risk.

Two days of dietary survey data is not at all reflective of someone’s regular eating patterns—and it definitely cannot be said that skipping breakfast twice causes heart disease.

As previous research—even press releases a few years ago from the American Heart Association—have touted the cardiometabolic benefits of intermittent fasting, this is another case of the media blowing things out of proportion.

That said, intermittent fasting is certainly not for everyone—especially women of reproductive age or those with a history of disordered eating.

Some downsides of intermittent fasting can include under-eating calories and nutrients, increased cortisol levels, dysregulated thyroid and sex hormones, and increased fatigue and stress.

Overall, while it’s possible that these results are accurate, we would need randomized controlled trials that split people into fasting and non-fasting groups to see if 8-hour eating windows do, in fact, increase the risk of heart disease-related mortality.

Subscribe now and never miss anything about the topics important to you and your health.