Talk to a Registered Dietitian and use INSIDER20 for 20% off!

Talk to a real Dietitian for only $99: Schedule Now

This post contains links through which we may earn a small commission should you make a purchase from a brand. This in no way affects our ability to objectively critique the products and brands we review.

Evidence Based Research To fulfill our commitment to bringing our audience accurate and insightful content, our expert writers and medical reviewers rely on carefully curated research.

Read Our Editorial Policy

Although most people tend to encounter seaweed only when wrapped around a sushi roll, edible sea plants have been consumed for thousands of years in coastal areas—like Japan, where seaweed residue has been found in clay pots dating as far back as 3000 BC.

Despite this lengthy history, one specific type of seaweed called sea moss has only recently started trending in the United States—and we can probably thank Kim Kardashian for that, as she popularized this ingredient in her sea moss smoothies.

But while we don’t typically rush to the Kardashians for health advice, she may be right with this one.

In this article, learn more about the purported health benefits of sea moss, from gut health to blood sugar regulation to body composition.

Get a science-backed calorie & macro plan, built for your life.

Get a science-backed calorie & macro plan, built for your life.

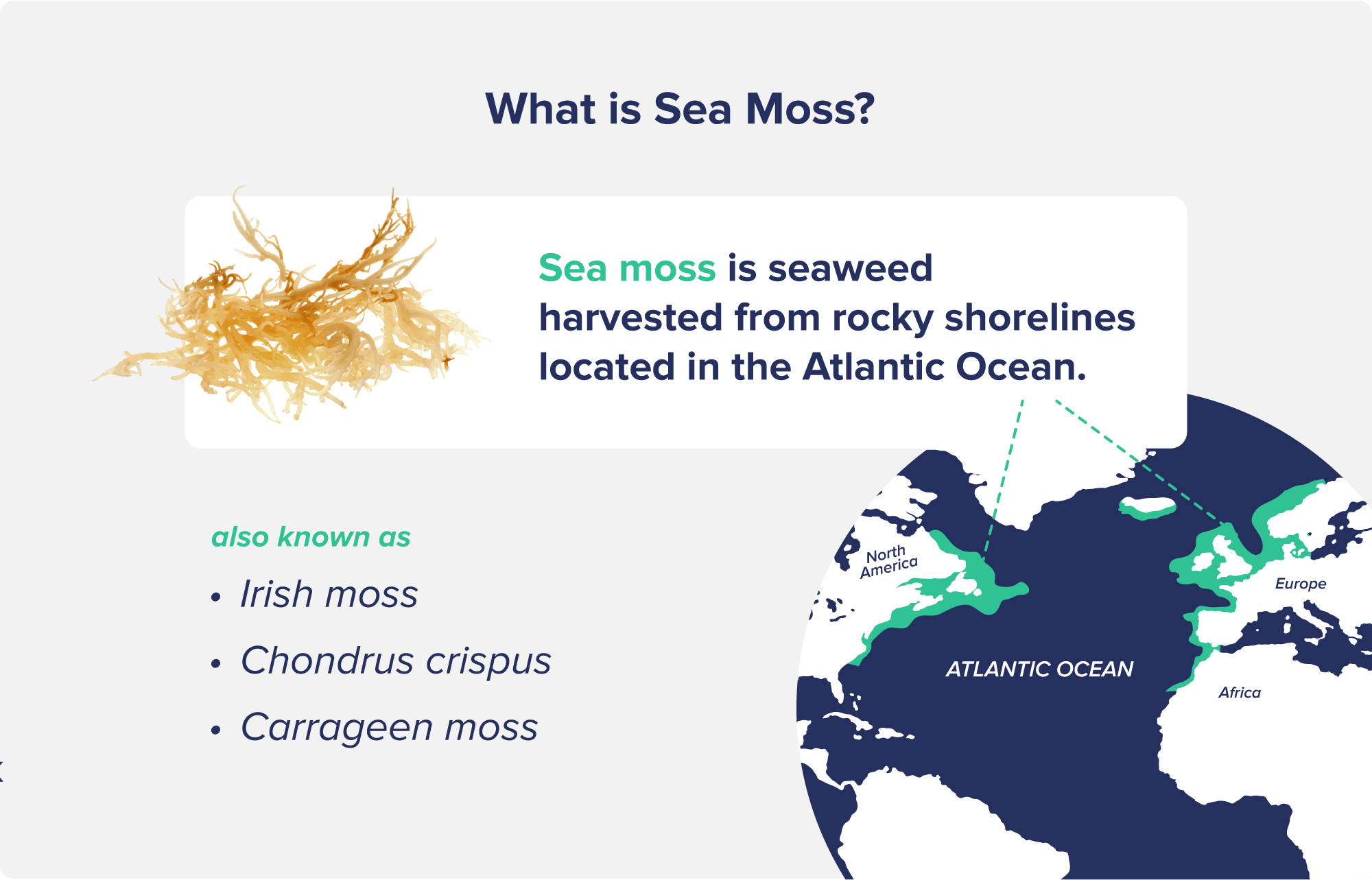

Sea moss—also known as Irish sea moss or in the scientific crowd as Chondrus crispus—is a type of seaweed harvested from the rocky coasts of the Atlantic Ocean between Europe and North America.

Although sea moss can grow in a handful of different hues, the most common variety is red sea moss.

Like dulse and nori, sea moss has been used for thousands of years—both for culinary and medicinal purposes.

During the 1800s, the food scarcity of the Irish Potato Famine led to people adding red sea moss to warmed milk with sugar—hence the “Irish sea moss” name.

Although you can certainly still eat sea moss, most people nowadays take sea moss in powdered or supplement form.

In fact, you’ve probably already consumed sea moss in the form of carrageenan.

Carrageenan is made from sea moss—the name comes from Carrigan Head in Northern Ireland—and is a thickening and emulsifying agent found in hundreds of foods, including almond milk, ice cream, and processed dairy products.

As a quick aside, carrageenan has been questioned for potentially causing gut inflammation or cancer in animals.

However, this has been refuted, as the “bad” form is actually poligeenan, not the carrageenan found in seaweed.

Plus, food additives, in general, are a different story than when a compound is simply found in its natural form.

Red sea moss is rich in minerals but has few calories and macronutrients.

Notably, sea moss contains calcium, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, zinc, and iodine, with each ounce containing around 47 mcg of iodine—about one-third of the recommended daily intake for adults.

Additionally, red sea moss contains antioxidants that protect our cells from oxidative damage, including lutein, β-carotene, astaxanthin, violaxanthin, neoxanthin, and zeaxanthin.

While we don’t have abundant scientific evidence about sea moss and human health, some studies have pointed to the potential benefits of it—and even more research has been done on the vast category of edible seaweeds.

Edible seaweeds like sea moss are rich in prebiotics—fibrous compounds that support the growth and survival of probiotics (healthy bacteria) in our digestive tracts.

The most prevalent prebiotics in red seaweed are polysaccharides like xylan, agar, carrageenan, and porphryan.

Seaweed polysaccharides have been found to host digestive enzymes, act as substrates for beneficial microbes to populate the gut, and promote short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production—compounds that reduce inflammation and support gut, brain, and metabolic health.

Even though some debunked studies claimed that carrageenan increased gut inflammation, more recent research has found the opposite.

In this study, rats fed carrageenan-rich sea moss had significantly increased SCFA production and the probiotic Bifidobacterium breve with reductions in pathogenic bacteria like Clostridium septicum and Streptococcus pneumonia.

Plus, the rats saw significant improvement in their colonic morphology after consuming sea moss for 21 days, indicating a more normal shape, structure, form, and size of colon cells.

Research also reports that Chondrus crispus-derived carrageenan has been used historically for its mucilaginous qualities to fight diarrhea, dysentery, and gastric ulcers.

Research over the past decades has suggested that seaweed consumption may be able to prevent or delay neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease.

In a 2015 study published in the journal Marine Drugs, red sea moss was found to have significant protective effects against β-amyloid-induced toxicity in the roundworm, a commonly used animal model to study aging and disease.

As β-amyloid plaque buildup is indicative of neurodegeneration, this research suggests that sea moss may protect brain health with age.

Another study found that sea moss protected against signs of Parkinson’s disease in roundworms, including reducing the accumulation of the toxic α-synuclein protein and correcting Parkinson’s-related slowness of movement.

However, these results are only in roundworms and have yet to be replicated in larger species or humans.

All seaweeds are rich in iodine, a mineral necessary for healthy thyroid function and thyroid hormone synthesis.

Even a minor iodine deficiency can cause adverse thyroid-related health conditions like goiter and hypothyroidism—but excessive iodine intake can do the same.

Therefore, moderate consumption of iodine-rich foods like seaweed can be beneficial—especially in countries that don’t utilize iodized salt.

In one study published in the British Journal of Nutrition, women with low iodine status who supplemented with 1g of seaweed had normalized thyroid hormone levels.

However, seaweeds other than sea moss are more likely to cause iodine toxicity if consumed excessively, including kombu and wakame.

Kombu is particularly iodine-rich, at 2,660µg per gram.

For reference, the Recommended Dietary Allowance for iodine for adults is 150 μg per day, and the tolerable upper intake level (UL) is 1,100mcg per day.

However, it’s worth noting that the average Japanese diet contains around 5g of seaweed per day, with iodine levels reaching 1,000-3,000µg.

Overall, sea moss does not contain as much iodine as other edible seaweeds, and moderate sea moss consumption—about 500-2000mg per day—is thought to provide healthy amounts of iodine.

According to a 2020 study, you would need to consume 286g per day of Irish sea moss to exceed the UL for iodine in adults.

Sea moss consumption may help improve body composition and metabolic health, including weight and body fat reduction and lower blood sugar.

Although there is no evidence looking directly at sea moss, there is research on another type of red seaweed (Grateloupia elliptica, from Jeju Island in Korea).

The study found that obese mice consuming this seaweed had significantly reduced body weight, white adipose tissue, fatty liver markers, and serum triglyceride levels.

Another Japanese red seaweed known as egonori exhibited anti-obesity effects in this study, including reducing body weight and white adipose tissue, ameliorating insulin resistance and high blood sugar, and reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine levels.

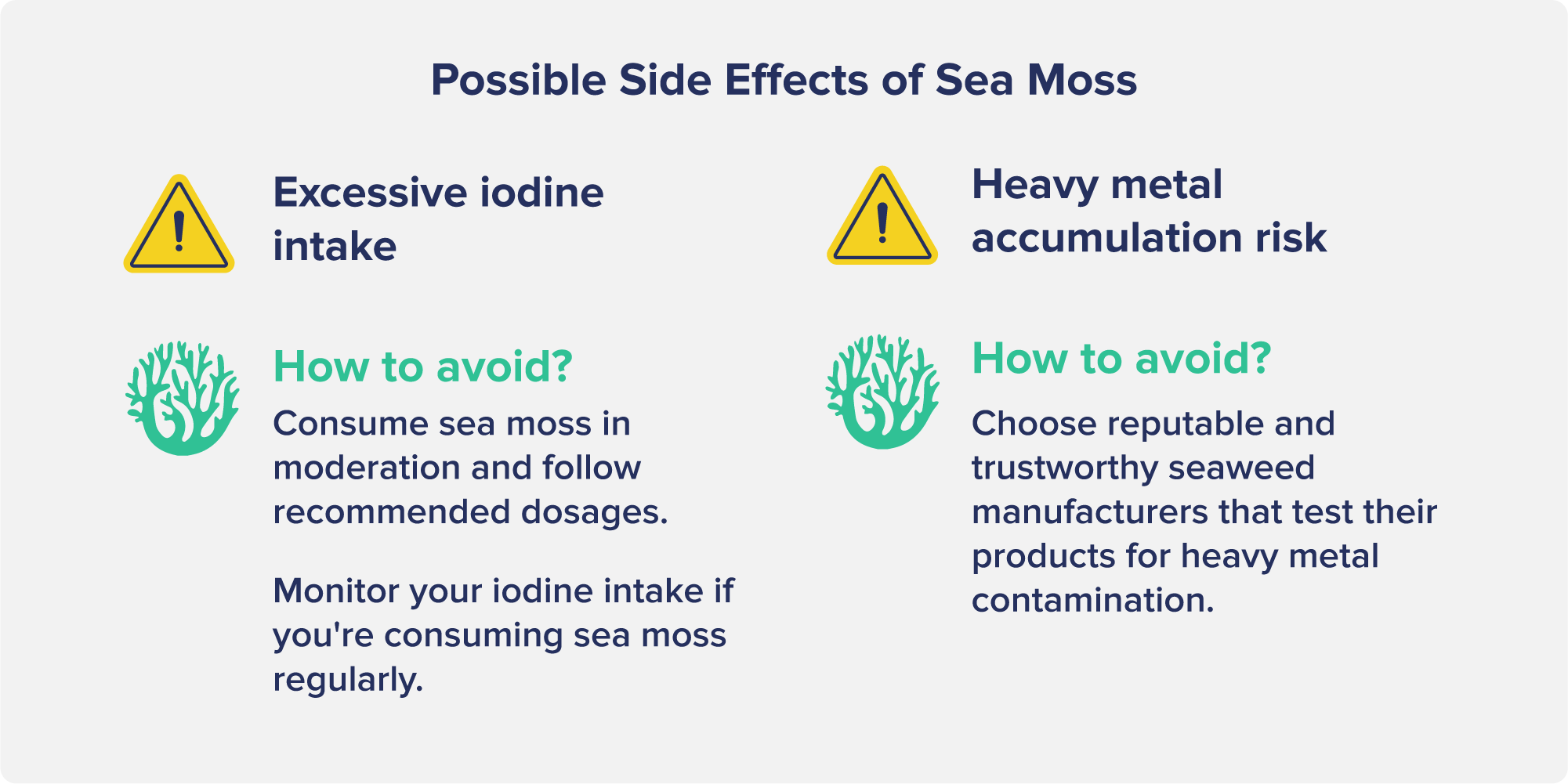

As mentioned, there are health risks associated with consuming too much seaweed, including excessive iodine intake that may affect thyroid health.

A study from 2020 looked at iodine levels in 30 samples of red seaweed, finding that consumption of 4g per day would not pose a health risk.

Another potential downside is heavy metal accumulation—a risk when consuming any ocean food.

However, sea moss has not been shown to have heavy metal accumulation, and many seaweed manufacturers test seaweed samples to ensure their safety.

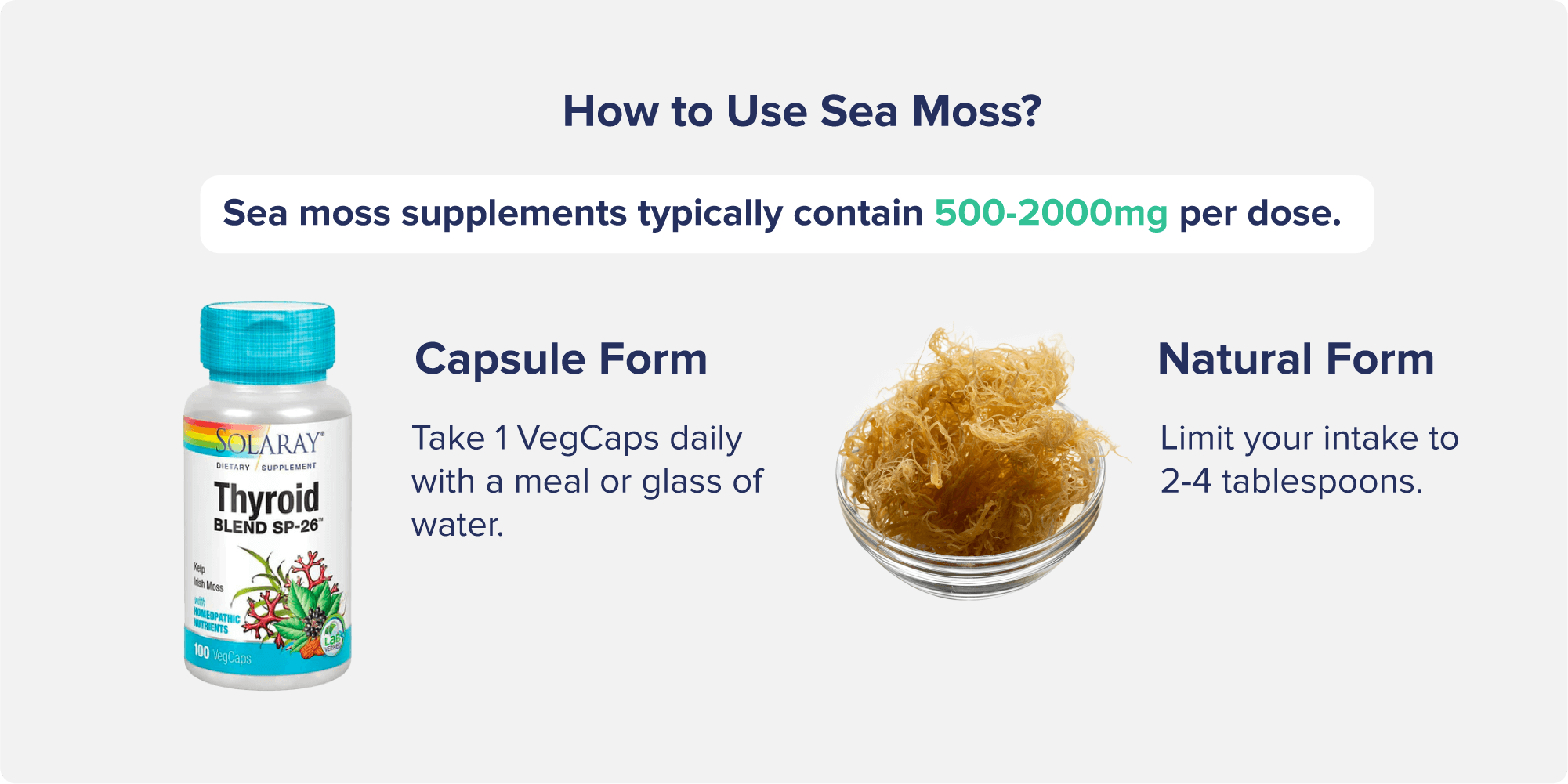

While you can consume sea moss directly, many people opt for supplements, powder, or sea moss gel.

As with any supplement, ensure that the manufacturer follows good practices, like being GMP-certified in an FDA-registered facility.

Plus, as seaweed is prone to heavy metal accumulation, check for third-party testing on any sea moss supplement.

Some supplements combine sea moss with other ingredients, like Solaray Thyroid Blend SP-26, which also contains kelp, eleuthero (an adaptogenic herb), gentian root, fenugreek, and cayenne pepper to support healthy thyroid and digestive function.

If you’re consuming sea moss in its natural form or sea moss gel, stick to a serving of 2-4 tablespoons.

Sea moss supplements typically contain 500-2000mg per dose.

If you take moderate amounts of sea moss every day, you may experience health benefits related to digestive, cognitive, thyroid, and metabolic functions.

Taking excessive amounts of sea moss every day—more than 286g per day—can lead to detrimental thyroid effects due to excessive iodine levels.

People who already have thyroid disorders or take thyroid medications should not take sea moss.

People who take blood thinners should be cautious with sea moss, as it can further thin blood.

Sea moss can also lower blood sugar and may lower blood pressure, so people on medications for these conditions should talk with their healthcare provider.

Pregnant and breastfeeding women should also avoid sea moss, as there is not enough research on its effects.

Sea moss can be consumed at any time of day as there is no known advantage to taking it at a particular time.

Cheong KL, Qiu HM, Du H, Liu Y, Khan BM. Oligosaccharides Derived from Red Seaweed: Production, Properties, and Potential Health and Cosmetic Applications. Molecules. 2018;23(10):2451. Published 2018 Sep 25. doi:10.3390/molecules23102451

Cherry P, Yadav S, Strain CR, et al. Prebiotics from Seaweeds: An Ocean of Opportunity?. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(6):327. Published 2019 Jun 1. doi:10.3390/md17060327

Cohen SM, Ito N. A critical review of the toxicological effects of carrageenan and processed eucheuma seaweed on the gastrointestinal tract. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2002;32(5):413-444. doi:10.1080/20024091064282

Combet E, Ma ZF, Cousins F, Thompson B, Lean ME. Low-level seaweed supplementation improves iodine status in iodine-insufficient women. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(5):753-761. doi:10.1017/S0007114514001573

Darias-Rosales J, Rubio C, Gutiérrez ÁJ, Paz S, Hardisson A. Risk assessment of iodine intake from the consumption of red seaweeds (Palmaria palmata and Chondrus crispus). Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020;27(36):45737-45741. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-10478-9

González-Bosch C, Boorman E, Zunszain PA, Mann GE. Short-chain fatty acids as modulators of redox signaling in health and disease. Redox Biol. 2021;47:102165. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2021.102165

Lee HG, Lu YA, Li X, et al. Anti-Obesity Effects of Grateloupia elliptica, a Red Seaweed, in Mice with High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity via Suppression of Adipogenic Factors in White Adipose Tissue and Increased Thermogenic Factors in Brown Adipose Tissue. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):308. Published 2020 Jan 24. doi:10.3390/nu12020308

Liu J, Banskota AH, Critchley AT, Hafting J, Prithiviraj B. Neuroprotective effects of the cultivated Chondrus crispus in a C. elegans model of Parkinson’s disease. Mar Drugs. 2015;13(4):2250-2266. Published 2015 Apr 14. doi:10.3390/md13042250

Liu J, Kandasamy S, Zhang J, et al. Prebiotic effects of diet supplemented with the cultivated red seaweed Chondrus crispus or with fructo-oligo-saccharide on host immunity, colonic microbiota, and gut microbial metabolites. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:279. Published 2015 Aug 14. doi:10.1186/s12906-015-0802-5

Lomartire S, Marques JC, Gonçalves AMM. An Overview to the Health Benefits of Seaweeds Consumption. Mar Drugs. 2021;19(6):341. Published 2021 Jun 15. doi:10.3390/md19060341

Murakami S, Hirazawa C, Yoshikawa R, et al. Edible red seaweed Campylaephora hypnaeoides J. Agardh alleviates obesity and related metabolic disorders in mice by suppressing oxidative stress and inflammatory response. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2022;19(1):4. Published 2022 Jan 8. doi:10.1186/s12986-021-00633-5

Sangha JS, Wally O, Banskota AH, et al. A Cultivated Form of a Red Seaweed (Chondrus crispus), Suppresses β-Amyloid-Induced Paralysis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mar Drugs. 2015;13(10):6407-6424. Published 2015 Oct 20. doi:10.3390/md13106407

Tobacman JK. Review of harmful gastrointestinal effects of carrageenan in animal experiments. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109(10):983-994. doi:10.1289/ehp.01109983