This post contains links through which we may earn a small commission should you make a purchase from a brand. This in no way affects our ability to objectively critique the products and brands we review.

Digestive System Disruptions: How Does Alcohol Affect Your Gut?

Evidence Based Research To fulfill our commitment to bringing our audience accurate and insightful content, our expert writers and medical reviewers rely on carefully curated research.

Read Our Editorial Policy

Many people know firsthand that alcohol affects their gut, causing reflux, indigestion, or stomach aches after a night of drinking.

But alcohol can impact more than just your next-day bathroom habits—it can also have longer-lasting effects on your stomach, esophagus, intestines, and more.

Let’s take a trip down the digestive tract (Ms. Frizzle style) and see how alcohol interacts with each part of the gut and what issues it can lead to.

End the Bloat Saga

Map your microbiome triggers and eat without fear.

End the Bloat Saga

Map your microbiome triggers and eat without fear.

How Does Alcohol Affect the Gut?

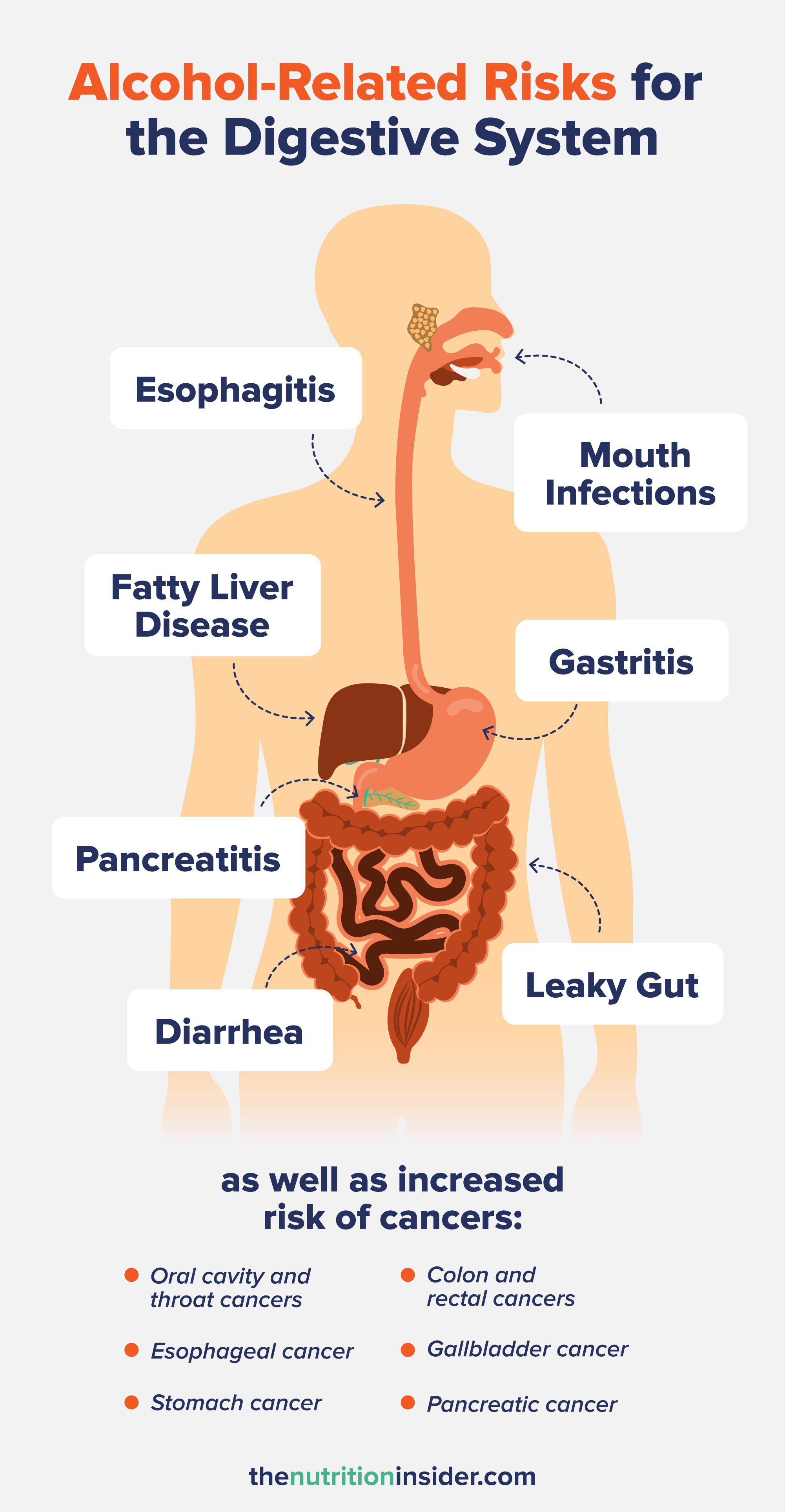

You may think of the gut mainly as your stomach, but the digestive tract also includes the mouth, esophagus, pharynx (throat), small intestines, large intestines (colon), and rectum. Other organs considered a part of the digestive system are the pancreas, gallbladder, and liver.

Any and all of these organs can be affected by excessive alcohol consumption or chronic alcohol abuse. Most of the digestive system organs are particularly prone to alcohol damage because alcohol interacts directly with their thin mucus membranes or linings. These soft tissues that line the digestive tract can be easily damaged, leading to inflammatory gut conditions, irritation, and cancer cell growth.1

The oral cavity (mouth), pharynx, esophagus, and stomach are the organs exposed to pure alcohol immediately after its ingestion, meaning they tend to take the brunt of the damage. However, excessive alcohol consumption can also cause digestive problems throughout the entire gut, leading to an increased incidence of many gut-related disorders and symptoms.

Alcohol and the Oral Cavity

Starting in the mouth, where all food and beverages start their journey through your GI tract, alcohol interacts with your tongue, gums, lips, and insides of cheeks. Alcohol dries out the mouth and can damage the sensitive mucosal linings and salivary glands, leading to inflammation and oral lesions.2

The antiseptic effect of alcohol also kills off healthy bacteria in the mouth (and in the colon), disrupting the oral microbiome and contributing to mouth and teeth infections or gum disease.2

Alcohol is significantly associated with an increased risk of head and neck cancers (a general term that includes cancers of the oral cavity, mouth, larynx, pharynx, esophagus, and salivary glands).3

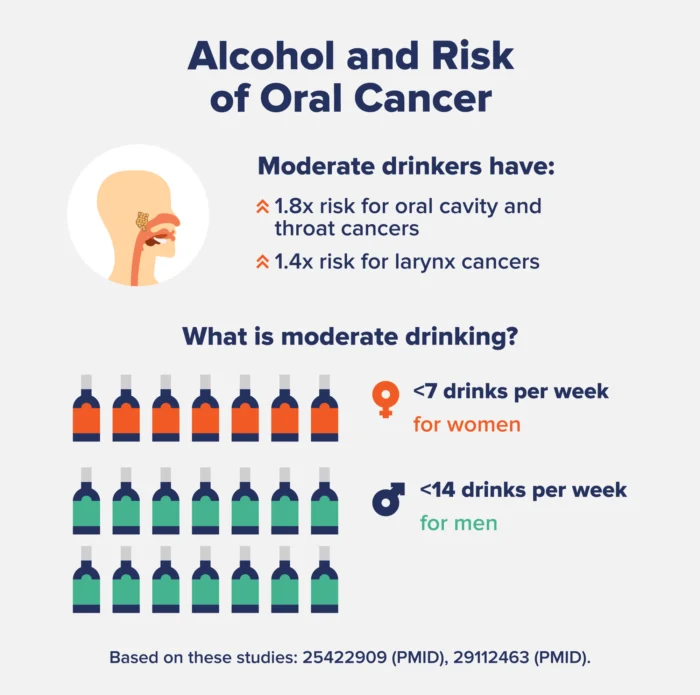

According to the National Cancer Institute, moderate drinkers (<7 drinks per week for women and <14 drinks per week for men) have a 1.8-fold increased risk of oral cavity and throat cancers and a 1.4-fold higher risk of larynx cancers than non-drinkers.4

Heavy drinkers (>7/week for women and >14/week for men) have a 5-times higher risk of oral cavity and throat cancers and a 2.6-times greater risk of larynx cancer.4

Alcohol and the Esophagus

Next comes the esophagus, which can also be heavily harmed by excess alcohol consumption. Even just one episode of binge drinking can significantly weaken the upper or lower esophageal sphincter—the muscles at the top and bottom of the esophagus that open and close to allow food and drink to pass through.1

A weakened lower esophageal sphincter is almost always a cause of acid reflux and heartburn, as the muscles are too weak to prevent food or drink from returning up from the stomach into the throat, causing that burning feeling.

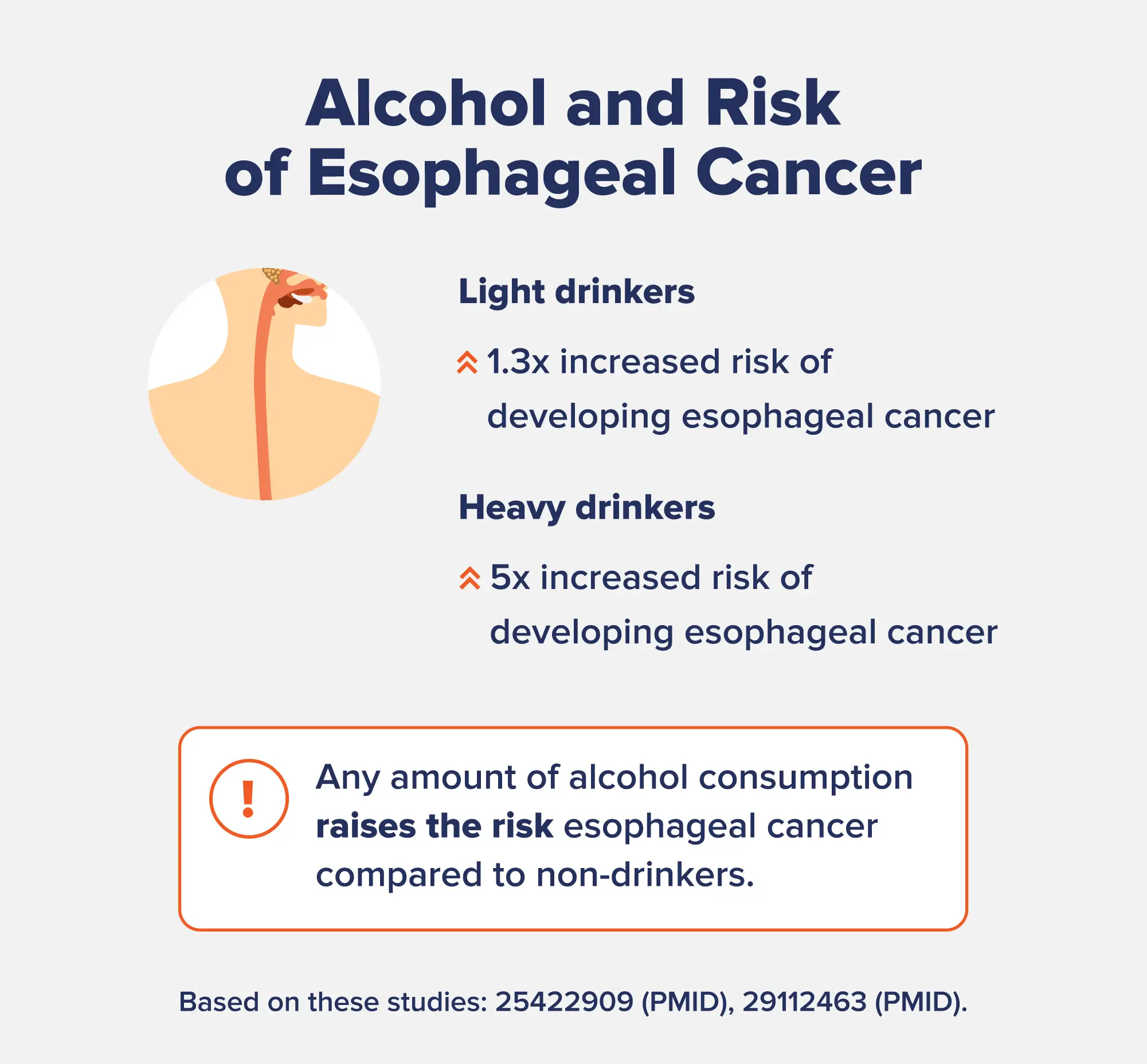

Heavy and chronic alcohol consumption can also cause esophagitis (inflammation of the mucosal lining in the esophagus), causing the esophagus to feel raw, sore, or burning.5 Alcohol increases the risk of esophageal cancer, especially a type called esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Unlike some other cancers, any amount of alcohol consumption increases the risk of this cancer. Compared to people who don’t drink, the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma increases by 1.3-fold for light drinkers and almost 5-fold for heavy drinkers.4

Alcohol and the Stomach

Alcohol then reaches the stomach, where it enters the bloodstream into circulation before heading to the liver. Here, alcohol irritates cells in the stomach lining and can induce mucosal defects and damage that can lead to gastrointestinal tract bleeding, lesions, and ulcers.

Drinking alcohol also impacts stomach acid production. Some people have elevated stomach acid production, leading to acute abdominal discomfort, pain, reflux, peptic ulcers, or gastritis. Others have low stomach acid production from drinking alcohol, meaning they can’t properly digest food and absorb nutrients, leading to indigestion.6

Alcohol consumption is linked to an increased risk of gastritis and gastric ulcers, which are slightly different from one another.7 Gastritis (also known as acute gastric mucosal injury) is a generalized stomach lining inflammation that can progress to deeper lesions and bleeding if left untreated.1

Research shows that just one episode of heavy drinking can induce these gastric mucosal injuries, and taking NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) can aggravate the gastric lesions and promote inflammation further—so be wary of popping an ibuprofen after a night out.1

Conversely, gastric or stomach ulcers are open sores that develop in the lining of the stomach, causing severe abdominal pain and a risk of serious internal bleeding. However, both can be caused by a disrupted stomach acid balance and inflammation of the stomach lining, which we know alcohol contributes to.5As you can probably guess, alcohol also increases the risk of stomach cancer. According to a meta-analysis of 10 studies, drinking alcohol was found to elevate gastric cancer risk by 39% compared to not drinking at all.8

Alcohol and the Intestines

In the intestines, alcohol kills beneficial bacteria, leading to gut dysbiosis. It also promotes inflammation in parts of both the small and large intestines, known as duodenitis and colitis, respectively.9

Alcohol can increase intestinal hyperpermeability. This is also known as leaky gut, a condition where the intestinal lining has “leaks” that allow harmful bacteria and toxins into the bloodstream.10

While some alcohol is absorbed into the bloodstream in the small intestine, it does not directly reach the large intestines (colon). Rather, alcohol can be transported to the colon through the bloodstream. After absorption into the colon, alcohol is metabolized via bacteria and the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) into acetaldehyde—the toxic, carcinogenic intermediary byproduct of alcohol metabolism.1

This is the primary way that liver cells metabolize alcohol, but the same enzymes are present in smaller amounts in the intestinal mucosal lining. The next step in this process is for the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) to convert acetaldehyde into acetate, but ALDH levels in the colon are low. Therefore, acetaldehyde can accumulate in the large intestine, contributing to alcohol-induced diarrhea, intestinal inflammation, and an increased risk of bowel cancers.1

Compared to non-drinkers, moderate or heavy alcohol consumption is linked to a 1.2- to 1.5-fold increased risk of colon and rectal cancers.4

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, is also impacted by alcohol intake. There are several mechanisms at play here, including the disruption to the gut microbiome, intestinal barrier permeability, inflammation, and elevated immune activation.11

Symptoms and flares in IBD patients can also be worsened by alcohol, including a higher risk of relapse in people with ulcerative colitis.12

Alcohol and the Liver, Pancreas, and Gallbladder

Many people don’t know that the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are also part of the digestive system (in addition to the biliary system).

It’s pretty well-known that alcohol misuse is hard on the liver (as are other toxic substances). Briefly, alcohol-induced liver damage can include several stages of liver disease: fatty liver, alcoholic steatohepatitis (liver inflammation), fibrosis, liver cirrhosis, and liver failure.

For an in-depth look at how chronic alcohol misuse affects the liver, check out this article.

Pancreatic function is also impacted by heavy alcohol consumption, including chronic and acute pancreatitis and pancreatic insufficiency.1 Accumulating evidence is also showing a link between alcohol and pancreatic cancer.4

Lastly, alcohol can damage the gallbladder (the small organ under the liver that stores bile and helps digest fat) by promoting inflammation. While the research is mixed on whether moderate alcohol consumption helps or harms gallstone formation, the evidence suggests that alcohol is linked to an increased risk of gallbladder cancer.13,14

A very important disclaimer: If you are dependent on alcohol or think you might have an alcohol use disorder, do not attempt to stop drinking alcohol on your own. It’s dangerous to quit alcohol cold turkey without medical supervision, as severe alcohol withdrawal symptoms can occur and be life-threatening. Please call the SAMHSA National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357) if you need help with mental health services, alcohol abuse, or substance abuse.

Alcohol and the Gut FAQs

How can I protect my gut from alcohol?

The answer you probably don’t want to hear is that the only way to protect your gut from alcohol completely is by not drinking. However, there are some ways to reduce the impact: don’t drink alcohol on an empty stomach; drink water in between each drink; don’t take NSAIDs like ibuprofen when you’re drinking; take probiotics or eat probiotic-rich foods (like yogurt and sauerkraut); eat prebiotic-rich foods like garlic, onions, leeks, and oats; and try to moderate your alcohol consumption.

How long does it take for gut bacteria to recover after alcohol?

It will be different for everybody, but one study found that after three weeks of alcohol abstinence, people’s gut microbiomes had not yet recovered. After stopping drinking, it likely takes at least a month to regain healthy gut bacteria and reduce dysbiosis fully. However, you may see signs of recovery within 2 to 3 weeks of quitting.15

What happens to the digestive system when you stop drinking alcohol?

The gut can recover pretty quickly once alcohol is taken out of the equation. One study found that just three weeks after people with alcohol use disorder removed alcohol, their gut barrier function was completely recovered, indicating that leaky gut was no longer present. However, while the abstainers had increased beneficial bacteria in their guts, the microbiomes were not entirely restored, suggesting that it takes longer than three weeks to reverse microbial damage. Other symptoms, like stomach aches, bloating, and heartburn, may resolve in as little as a few days to a couple of weeks after quitting alcohol.15

- Bode, C., & Bode, J. C. (1997). Alcohol’s role in gastrointestinal tract disorders. Alcohol health and research world, 21(1), 76–83.

- Riedel, F., Goessler, U. R., & Hormann, K. (2005). Alcohol-related diseases of the mouth and throat. Digestive diseases (Basel, Switzerland), 23(3-4), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1159/000090166

- National Cancer Institute. (2021). Head and Neck Cancers. https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/head-neck-fact-sheet

- National Cancer Institute. Alcohol and Cancer Risk. (2021). https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/alcohol/alcohol-fact-sheet

- Rocco, A., Compare, D., Angrisani, D., Sanduzzi Zamparelli, M., & Nardone, G. (2014). Alcoholic disease: liver and beyond. World journal of gastroenterology, 20(40), 14652–14659. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14652

- Chari, S., Teyssen, S., & Singer, M. V. (1993). Alcohol and gastric acid secretion in humans. Gut, 34(6), 843–847. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.34.6.843

- Roberts D. M. (1972). Chronic gastritis, alcohol, and non-ulcer dyspepsia. Gut, 13(10), 768–774. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.13.10.768

- Ma, K., Baloch, Z., He, T. T., & Xia, X. (2017). Alcohol Consumption and Gastric Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research, 23, 238–246. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.899423

- Engen, P. A., Green, S. J., Voigt, R. M., Forsyth, C. B., & Keshavarzian, A. (2015). The Gastrointestinal Microbiome: Alcohol Effects on the Composition of Intestinal Microbiota. Alcohol research : current reviews, 37(2), 223–236.

- Bishehsari, F., Magno, E., Swanson, G., Desai, V., Voigt, R. M., Forsyth, C. B., & Keshavarzian, A. (2017). Alcohol and Gut-Derived Inflammation. Alcohol research : current reviews, 38(2), 163–171.

- White, B. A., Ramos, G. P., & Kane, S. (2022). The Impact of Alcohol in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflammatory bowel diseases, 28(3), 466–473. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izab089

- Jowett, S. L., Seal, C. J., Pearce, M. S., Phillips, E., Gregory, W., Barton, J. R., & Welfare, M. R. (2004). Influence of dietary factors on the clinical course of ulcerative colitis: a prospective cohort study. Gut, 53(10), 1479–1484. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2003.024828

- Leclercq, S., Matamoros, S., Cani, P. D., Neyrinck, A. M., Jamar, F., Stärkel, P., Windey, K., Tremaroli, V., Bäckhed, F., Verbeke, K., de Timary, P., & Delzenne, N. M. (2014). Intestinal permeability, gut-bacterial dysbiosis, and behavioral markers of alcohol-dependence severity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(42), E4485–E4493. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1415174111

- Cha, B. H., Jang, M. J., & Lee, S. H. (2019). Alcohol Consumption Can Reduce the Risk of Gallstone Disease: A Systematic Review with a Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Case-Control and Cohort Studies. Gut and liver, 13(1), 114–131. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl18278

- Bagnardi, V., Rota, M., Botteri, E., Tramacere, I., Islami, F., Fedirko, V., Scotti, L., Jenab, M., Turati, F., Pasquali, E., Pelucchi, C., Galeone, C., Bellocco, R., Negri, E., Corrao, G., Boffetta, P., & La Vecchia, C. (2015). Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. British journal of cancer, 112(3), 580–593. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.579