Talk to a Registered Dietitian and use INSIDER20 for 20% off!

Talk to a real Dietitian for only $99: Schedule Now

This post contains links through which we may earn a small commission should you make a purchase from a brand. This in no way affects our ability to objectively critique the products and brands we review.

Evidence Based Research To fulfill our commitment to bringing our audience accurate and insightful content, our expert writers and medical reviewers rely on carefully curated research.

Read Our Editorial Policy

Autumn is a unique season, with September and early October often remaining in the warm grasp of summer, while later October and November bring cooler temperatures and even the first possibilities of snow in some regions.

Because of this variation in temperatures and climates, a wide variety of fall superfoods can be harvested throughout the season.

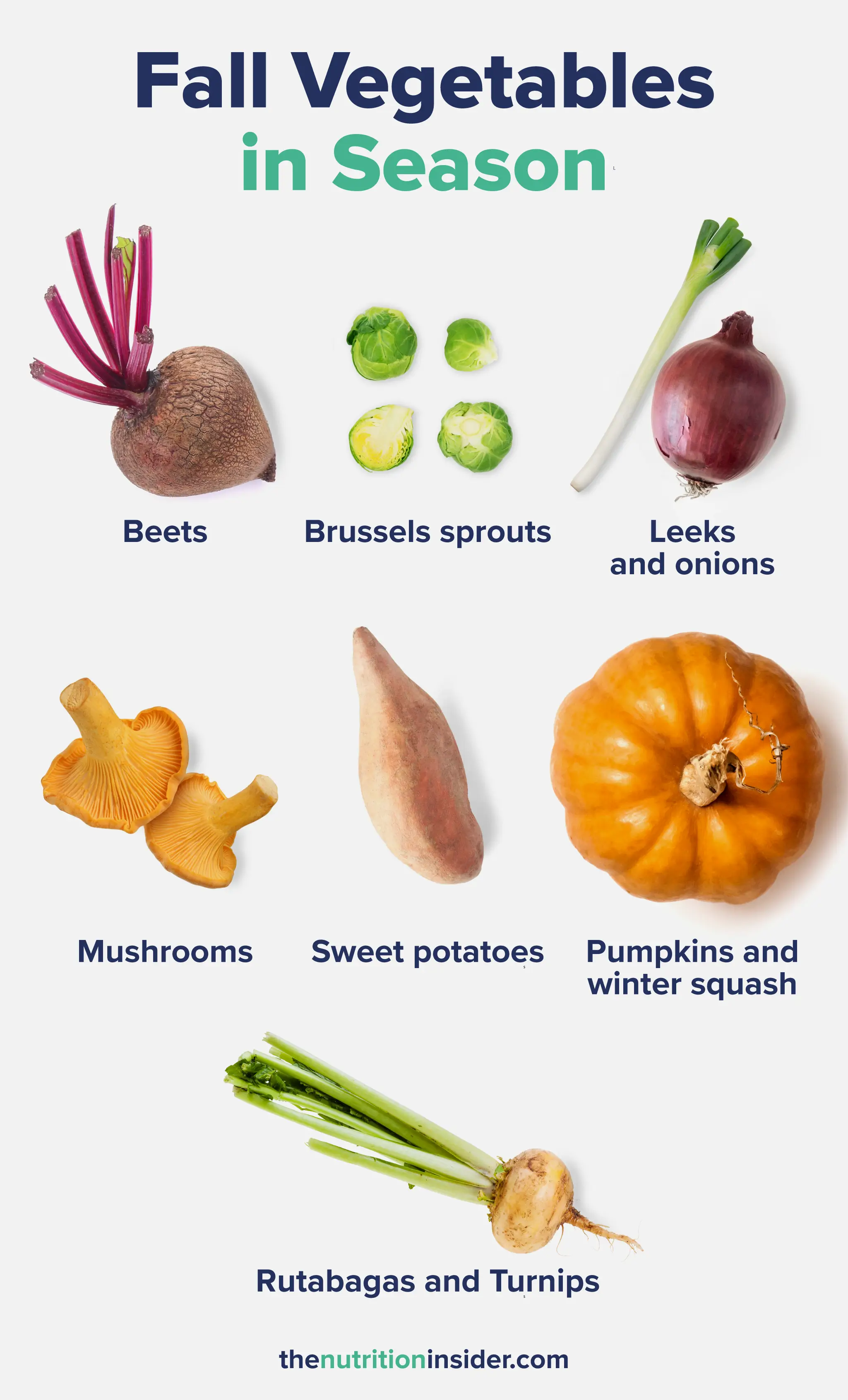

From pears and persimmons to beets and Brussels sprouts, dozens of seasonal fruits and vegetables reach their peak during the fall months—both in taste and nutritional value.

Although you can get most foods year-round in the United States, eating fruits and vegetables when they are in season can be an enlightening experience.

Compared to out-of-season produce at grocery stores, in-season and locally grown fruits and vegetables taste noticeably better (anyone who has ever tasted a fresh, farm-grown summer tomato can attest to this)—not to mention they are more beneficial for both your health and the environment.

This is because seasonal fruits and vegetables are grown during the times of the year with the best natural conditions for that specific crop. Not only do they taste better, but in-season produce is harvested at their peak ripeness level, translating to peak nutritional value.

Let’s look at a handful of the top fruits and veggies in season this fall.

A few notes: first, we’ll use the culinary definitions of fruits and vegetables, not the botanical ones. Second, as the climate of the United States can vary so widely from region to region, this is just a general list of what is typically in season in fall—your area may have different foods available.

From sweet and crisp apple pies and tart cranberry sauces to pomegranate seeds adorning harvest salads, these hearty autumnal fruits are perfect for brightening up cozy, warm dishes in the fall.

Apples are a quintessential autumnal fruit, perfect for apple crumbles, pies, cider, apple butter, caramel apples, and more.

Their harvest season typically runs from late summer to early fall (although many people who have gone apple picking in 85-degree September weather may wish the season was a bit later!).

While we can get a variety of apples year-round, they are only harvested in the fall and then stored throughout the year in cold storage facilities. Some apples in the grocery store have been picked an entire year before you purchase them! As you can imagine, freshly picked and locally harvested apples are much tastier, with crispier, juicier, and sweeter textures and flavors.

Prominent nutrients in apples include vitamin C, soluble fiber, and antioxidants—especially flavonoids like quercetin, chlorogenic acid, and catechins.

Some of the best apple varietals that go well with fall flavors and recipes include Granny Smith (best for apple pies), Honeycrisp (excellent fresh and in salads), Braeburn (great for baking), Pink Lady (great as a fresh, tart snack), Jonagold (good for cider), and McIntosh (great for apple butter and applesauce).

What’s Thanksgiving dinner without cranberry sauce? Fresh cranberry sauce does not compare to the canned version, imparting a tart flavor that helps cut through the richness of the gravies, turkey, potatoes, and casseroles on the table.

Cranberries are native to North America and typically are harvested in New England and the Midwest from mid-September through October.

Nutrients found in cranberries include vitamin C, fiber, manganese, and antioxidants like anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins (the same type found in blackberries, blueberries, and other deeply colored fruits and vegetables).

One of cranberry’s notable claims to fame is its link to urinary tract health, which includes reducing the risk of urinary tract infections (UTIs). This is not an old wive’s tale—cranberries really do help with UTIs, as the proanthocyanidin compounds prevent bacteria from sticking to the urothelial cells lining the bladder.1By the way, if you’re wondering why blueberries or other proanthocyanidin-rich foods don’t prevent UTIs, it’s because proanthocyanidins have “A” or “B” type linkages. Only those with A-type linkages, like those found in cranberries, prevent the adhesion of E. coli bacteria to the bladder wall.

Grapes ripen during the end of summer and early fall, with peak grape-eating and wine-harvesting times in the Northern Hemisphere occurring from August through October.

Although over 99% of grapes in the United States come from California, other states, like Washington, New York, and Texas, also grow grapes.

There are hundreds of grape varietals, but Concord, Sultana, Crimson, and Thompson are the most common grapes for eating.

Red grapes are the best food source of resveratrol—an antioxidant linked to heart health and longevity.2 Grapes also contain vitamins C and K and other antioxidants, like quercetin, catechins, and anthocyanins (in red, black, and purple grapes only).

Pears are another iconic fall fruit, with their sweet, juicy, and sometimes crisp texture pairing well with other fall flavors, including cinnamon, goat cheese, nuts, and baked desserts.

There are several pear varieties that ripen at slightly different times, but most of them are at their peak in the late summer through fall.

The most common pears are Bartlett (the classic pear with light green skin and soft, juicy flesh), Bosc (a slender, elongated, and brownish-skinned pear with crunchier, crisper texture), and Anjou (round and plump pears that can be either red or yellow, with textures in between the previous two).

Pears are excellent sources of dietary fiber, providing 5-6 grams per medium fruit. They also have vitamin C, a bit of potassium, and flavonoid antioxidants like catechins and quercetin.

Persimmons are a lesser-known but underrated fall fruit, only available in the late fall and early winter (typically October through December).

There are two main types of persimmons. Fuyu persimmons can be eaten like an apple—they are small, round, and pumpkin-colored orange, and have a sweet and crisp taste. Hachiya persimmons are more acorn-shaped and are reddish-orange. They need to fully ripen before eating, becoming very soft, sweet, and almost jelly-like inside.

Both types of persimmons are rich in vitamin C, beta-carotene (the precursor to vitamin A), manganese, and antioxidants like epicatechin, gallic acid, and tartaric acid.3

Another fruit associated with autumn and harvest season, pomegranates are most certainly a superfood due to their high antioxidant content. Pomegranates are rich sources of ellagitannins and anthocyanins, which fight oxidative stress and inflammation.

Some studies suggest that pomegranate (or its extract) exhibits anti-cancer activity, including in preventing breast, skin, lung, and prostate cancers.4

Fresh pomegranates are in season starting in October, typically through December. Unlike almost all other fruits, you only eat the seeds of the pomegranate—not the flesh.

Pomegranate seeds (also known as the arils) are perfect for adding a pop of color and tartness to autumn salads, and pomegranate juice can be used for sipping, smoothies, mocktails, baked goods, sauces, and marinades.

Beets are harvested in the late summer and early fall, and the long shelf life and hearty nature of this root vegetable have provided many people throughout history with nutrients and fibrous carbohydrates throughout long winters.

Beets and beet greens are highly nutritious, containing folate, potassium, and antioxidants, including betalain, epicatechin, and rutin.5 Beets are also a natural source of dietary nitrates, which convert into nitric oxide—a vasodilating compound that supports heart and vascular health.5

Their earthy and rich flavor and vibrant red hue are perfect for seasonal meals in the fall, including roasted beets in side dishes and salads, beetroot juice, or beet soup (Borscht).

Brussels sprouts are typically harvested from September to mid-February and can often last long—especially if the sprouts remain on their stalk. Uniquely, Brussels sprouts are considered to be the sweetest after a frost, which is why they can be harvested throughout the winter.

They are commonly used in fall recipes, as they are delicious roasted as a side dish, added to salads, or shaved (the best method for eating raw). Although they are on the bitter side, Brussels sprouts become sweeter and milder upon cooking—especially if you roast them until they caramelize.

Brussels sprouts are very nutritious, containing few calories, loads of vitamin C, fiber, vitamin K, and antioxidants like sulforaphane—a phytochemical found in cruciferous vegetables linked to cancer prevention, heart health, and cognitive function.6

These two vegetables are part of the Allium family and have peak harvest seasons in the autumn. Leeks are milder and sweeter than onions, which are sharper and more intense (especially when raw).

Leeks don’t last nearly as long as onions, typically lasting up to two weeks in the fridge (compared to onions’ potential to last several months in cool storage).

Both leeks and onions are low in carbohydrates and contain vitamin C, but onions contain more of the antioxidant quercetin. Red onions are also a source of anthocyanins—the same antioxidant found in cranberries and other berries.

Although not technically a vegetable, we tend to treat these fungi as veggies in the kitchen. Fall is considered wild mushroom foraging season, and many different types are ready for harvest in autumn.

Some mushrooms that are in season during fall include chanterelles, porcini, maitake, oyster, shitake, lion’s mane, enoki, and cremini (baby bella) mushrooms.

Mushrooms contain unique nutrients for a “vegetable,” including beta-glucan fiber, selenium, vitamin D (if grown in the sun), ergothioneine (an antioxidant linked to longevity), copper, and several B vitamins.7

Sweet potatoes (which are not even related to regular potatoes, by the way) are commonly associated with fall foods, such as sweet potato casserole or sweet potato pie.

Their sweet and creamy texture is ideal for roasting, baking, and pureeing, and they are typically harvested in late summer to early November.

Sweet potatoes are one of the richest sources of beta-carotene—a precursor to vitamin A linked to eye, immune, skin, and respiratory health. They also contain vitamin C, fiber, and potassium.

Although they are commonly spoken of as two different families, pumpkins are actually a type of squash.

Many winter squashes are also in season in fall, including pumpkin, acorn squash, spaghetti squash, butternut squash, kabocha squash, and delicata squash. All orange-fleshed squash contain beta-carotene, with pumpkin containing more than the others. For an in-depth look at the differences between pumpkin and squash, check out this article.

Turnips and rutabagas are both root vegetables in the Brassica family (the same as kale and Brussels sprouts) that are in season during fall and winter. While similar, they differ in flavor, appearance, and uses in the kitchen.

Rutabagas usually have yellow or purple skin with yellow-orange flesh and are also known as “yellow turnips” or “Swedes.” Conversely, turnips are smaller, with white flesh and whitish to pale purple skin.

While rutabagas are sweeter and milder (almost nutty) in flavor and need to be cooked, turnips can be eaten raw or cooked and have a slightly bitter and peppery taste (especially when raw).

Both of these root vegetables provide vitamin C, fiber, potassium, and loads of water, but rutabagas also have beta-carotene and folate.

Some other nutritious fruits and vegetables that are in season in fall (often in addition to other seasons) include:

Seasonal foods are consumed in the season they are harvested in. To eat seasonally, you would consume more fruits, vegetables, or other plants grown during specific times of the year when they are at their peak freshness. Each crop has different parameters that it grows best in, including preferences for sunlight, temperature, climate, or soil changes. Due to these seasonal differences, certain crops grow better in warmer weather, while others are best in damp, low-sun, or cold conditions.

Yes, there are many health benefits to eating seasonally. Seasonal fruits and vegetables are grown during the times of the year with the best natural conditions for that specific crop. Not only do they taste better, but in-season produce is harvested at their peak ripeness level, which translates to peak nutritional value. They have not been stored for long periods of time (some are often up to a year after being harvested) and don’t travel as far of a distance to get to your plate. Nutrients like vitamin C and antioxidants are typically the most affected by long storage times between harvesting and eating. Seasonal eating goes hand-in-hand with local eating—find seasonal foods at your local farmers market.

There are many superfoods you can eat in the cooler months of the fall season. Some of the most nutritious fall fruits are apples, cranberries, grapes, and pomegranates. Fall vegetables that are superfoods include beets, Brussels sprouts, onions, mushrooms, squash, sweet potato, dark leafy greens, and broccoli.