Talk to a Registered Dietitian and use INSIDER20 for 20% off!

Talk to a real Dietitian for only $99: Schedule Now

This post contains links through which we may earn a small commission should you make a purchase from a brand. This in no way affects our ability to objectively critique the products and brands we review.

Evidence Based Research To fulfill our commitment to bringing our audience accurate and insightful content, our expert writers and medical reviewers rely on carefully curated research.

Read Our Editorial Policy

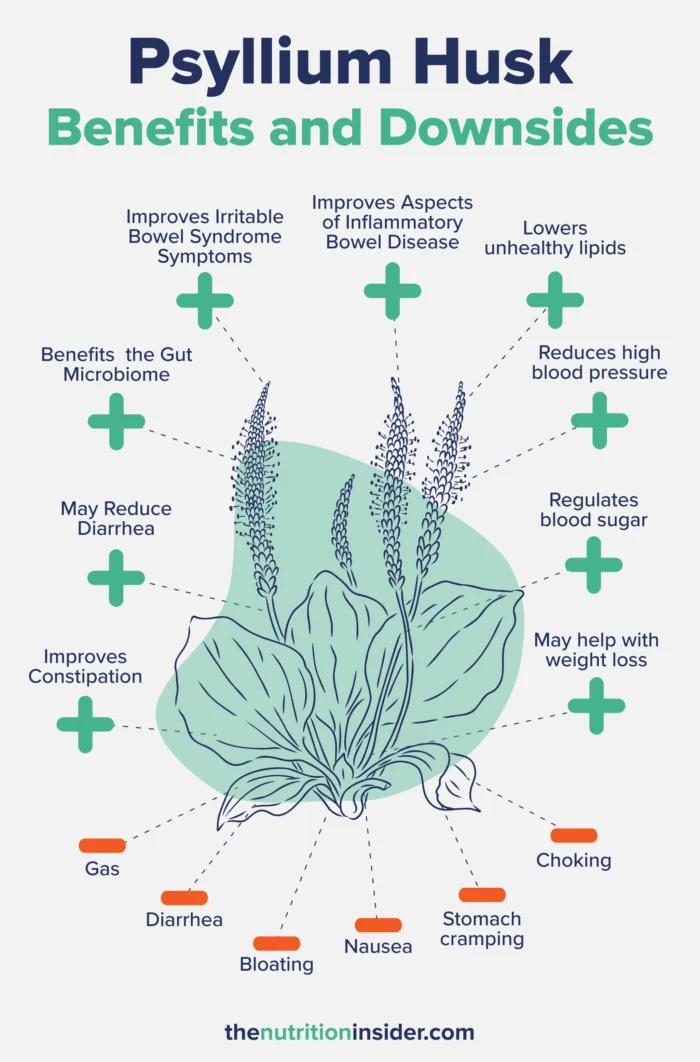

Psyllium husk is one of the best-studied types of dietary fiber, with benefits including constipation relief, gut microbiome diversity, cholesterol and blood sugar management, and weight loss.

Even if you’ve never heard of psyllium husk before, you have likely heard of products that use it, like Metamucil.

As a stool-softening mild laxative, psyllium husk has helped many people with constipation, but the gut-related benefits of psyllium extend even further than supporting regularity.

In this article, we’ll describe how psyllium husk works in the gut, the evidence-backed digestive benefits of psyllium, and notes on safety, dosages, and precautions.

Psyllium husk is a soluble fiber derived from the husks of the small, gel-coated seeds produced by a shrub-like plant called Plantago ovata.

Plantago ovata is a native Mediterranean plant known colloquially by many different names—including blond plantain, desert Indian wheat, blond psyllium, and ispaghol—and the husks and seeds are referred to as psyllium or ispaghula.

It’s commonly consumed as a powder that mixes with water, but you may also see whole psyllium husks, psyllium seeds, or capsules.

Psyllium husks are the outer covering of the seed and the type most used in fiber supplements, as they have a higher swelling index than the psyllium seed. This means the husk absorbs more water, making it more useful for digestion.

As a viscous soluble fiber, psyllium dissolves in water, becoming a gel-like substance in the gut.

This watery gel softens stool and swells to add extra bulk to bowel movements. The additional bulk stimulates the intestines to contract, helping to move things along in your intestinal tract.

The gel-like substance can regulate stool consistency from both sides, softening hard stools or “soaking up” excess moisture in liquidy diarrhea.

However, psyllium is not fermented in the gut like many other soluble fibers. While fermenting in the gut does have many health benefits, it’s thought that non-fermentable soluble fibers like psyllium are better for constipation. This is because they remain intact throughout the entire digestive system, bringing their watery gel to the colon to produce softer yet bulkier stools that are easier to pass.1

Long before we had research to back up its claims, psyllium had historically been used in traditional Chinese medicine for thousands of years. It then entered Western culture in the 16th century when European folk medicine noted psyllium as a constipation remedy and started to become a household name when Metamucil was introduced in the United States in 1934.

Psyllium fiber supplements have now been widely studied and used for their role in digestive health, especially constipation. Although psyllium husk is best known for helping with regularity, it can also benefit people with diarrhea, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and dysbiosis.

Soluble fiber is known to help with constipation, but it’s the viscous (gel-forming) nature of psyllium husk that makes it particularly beneficial as a natural laxative.

A study from 2021 randomized 79 adults with chronic constipation to consume either kiwifruit (2 per day), prunes (100g per day), or psyllium (12g per day) for four weeks. They found that all three treatments increased the number of bowel movements per week and reduced straining.2

In a 2021 systematic review published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, researchers gave psyllium a “Level II Evidence, Grade B Recommendation” for its effects on constipation relief, which means it has well-conducted studies but lacks enough randomized controlled trials.3

Alongside its laxative effects on constipation, psyllium has also been known to reduce hemorrhoids or anal fissures—two conditions exacerbated or caused by chronic constipation.

Overall, there is fairly strong evidence that psyllium husk improves constipation and increases stool frequency. That said, not all studies have shown benefits.

As psyllium husk has a noted laxative effect, you may wonder how it could help with diarrhea—which, most people would agree, is a condition that does not need a laxative supplement.

However, some research has shown that psyllium can improve stool consistency, adding bulk and reducing moisture in the less-formed, liquidy stools characteristic of diarrhea.4

However, some people do not tolerate psyllium well, and consuming too much can easily cause more diarrhea, so it’s important to start with a small amount.

Dysbiosis—an overabundance of harmful bacteria in the gut with too few beneficial bacteria—can contribute to just about all digestive problems, including constipation, diarrhea, IBS, and IBD.

As mentioned, psyllium husk is a viscous soluble fiber that does not get fermented by gut bacteria in the intestines. Fermentable fibers are known to benefit the gut microbiome by acting as prebiotics that feed the good bacteria in the gut, as well as producing short-chain fatty acids.

However, psyllium husk has still been found to improve aspects of gut microbial health despite its non-fermenting nature.In one small study, people who took psyllium for a week had increased stool water, which was associated with significant improvements in gut microbiota composition. The effects were greater in constipated people than in healthy people.5

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is characterized by constipation, diarrhea, or a combination of both.

As we’ve seen that psyllium may benefit both constipation and diarrhea, it makes sense that people with IBS with the same symptoms may also see improvements.

In a 2017 review article, researchers concluded that “Fiber supplementation, particularly psyllium, is both safe and effective in improving IBS symptoms globally.”6

One reason why psyllium is thought to work well with IBS patients is because of its non-fermenting nature. Although fermentable fibers are beneficial, they can cause gas and bloating when gut bacteria ferment them (i.e., break them down)—two common symptoms of IBS.

That said, not all studies have verified the benefits of psyllium on IBS, underlying the highly individualistic nature of the condition.7

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is comprised of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, two conditions that increase inflammation and ulcers in the intestines.

Although many people with IBD shy away from fiber, it’s typically insoluble fiber that causes the most discomfort.

Research has shown that psyllium husk may benefit people with mild-to-moderate Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis (UC), but people with more severe conditions may want to avoid it.

One older study in people with ulcerative colitis found that psyllium was as effective as mesalamine (a common prescription drug for UC) in maintaining remission.8

Like with IBS, the symptoms of IBD are highly individual, and not everyone will be able to tolerate psyllium husk.

The benefits of psyllium husk go beyond the gut, with research showing that it:

The dosage of psyllium supplements varies widely in studies, typically ranging from 3 grams per day to 15 grams. It’s best to start on the lowest end of the scale, following directions on the psyllium supplement you get. Typically, a dose will be ½ of a teaspoon to start, gradually increasing if you don’t have side effects.

It’s important to mix psyllium with enough water (or drink water alongside if they are capsules) because it needs liquid to absorb and swell in the correct amount and location. Without water, psyllium can swell in your throat and cause choking in extreme cases.

Side effects of psyllium are often the same symptoms people are trying to treat, including gas, diarrhea, bloating, nausea, and stomach cramping. These are most often seen at higher doses or in people with more sensitive gastrointestinal tracts.

Psyllium supplements can also interfere with the absorption of some medications, so speak with your doctor if you are unsure.

You should also not use psyllium if you have bowel obstructions, bowel spasms, esophageal structures, or any other narrowing or obstructions in the GI tract.

Lastly, people with kidney disease should talk to their doctor before taking psyllium.

Psyllium husk can cause digestive issues, especially in high doses. These include diarrhea, gas, bloating, stomach pain, and nausea. It can also, in extreme cases, cause choking if someone consumes psyllium husk powder without water.

It’s generally considered safe to take moderate amounts of fiber supplements like psyllium husk every day. However, you should ask your doctor about your specific health condition before using it. If you’re relying on it as a laxative to produce bowel movements, it’s typically not recommended to use for more than seven consecutive days.

Psyllium husk is made from the outer shells of the seeds of the plant Plantago ovata. Plantago ovata is a native Mediterranean plant also known as blond plantain, desert Indian wheat, blond psyllium, and ispaghol.

There does not appear to be a “best time” to take psyllium. If you are using it for constipation, you may want to use trial and error to see how long psyllium takes to work in your system and then base your dosage timing on that.