Save $40 on your initial consult with a TNI Dietitian!

Talk to a real Dietitian for only $99: Schedule Now

Evidence Based Research To fulfill our commitment to bringing our audience accurate and insightful content, our expert writers and medical reviewers rely on carefully curated research.

Read Our Editorial Policy

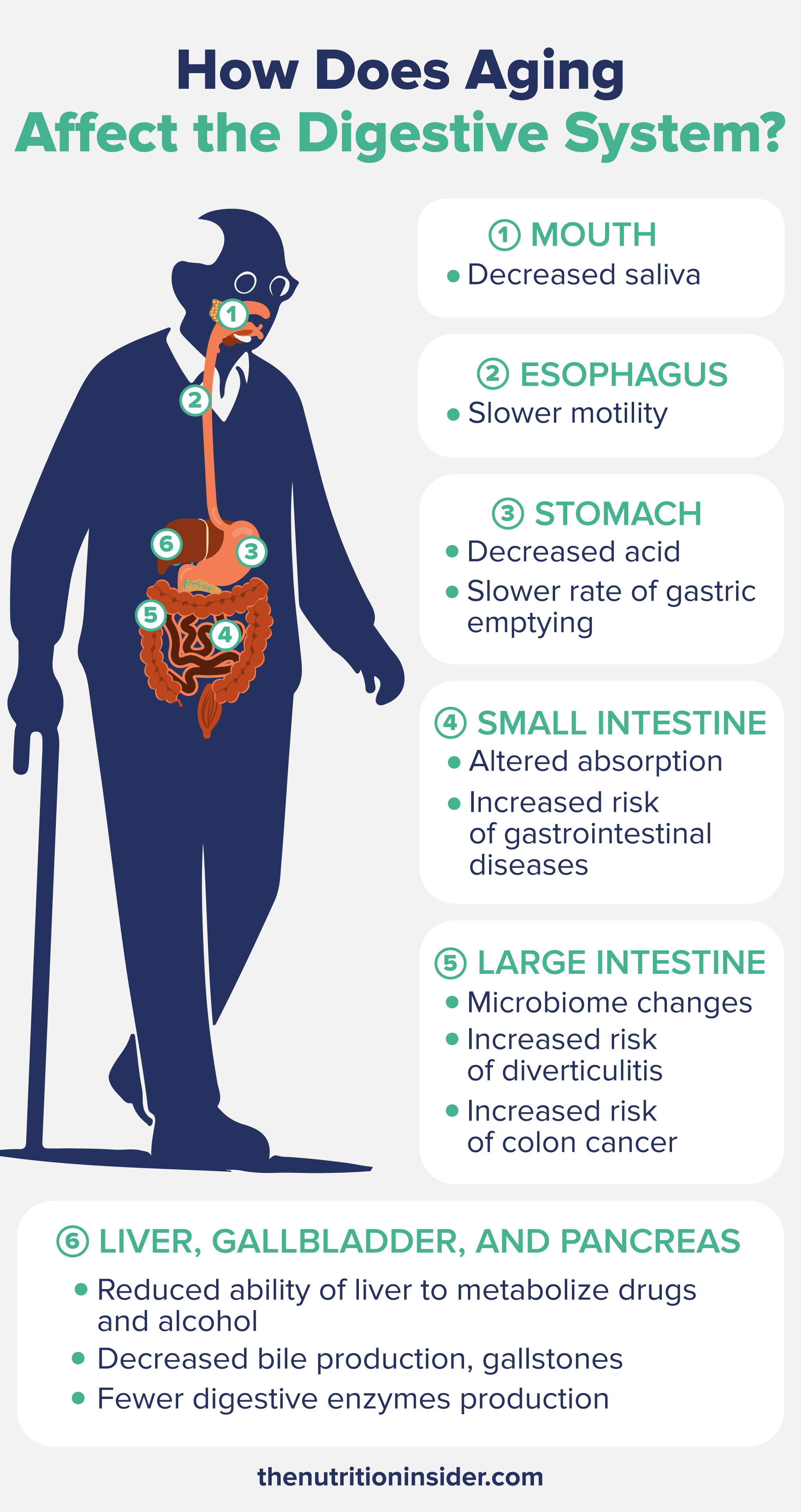

While the brain and the heart are the organs most people typically associate with dysfunction upon aging, the digestive system also undergoes plenty of age-related changes and conditions.

With changes including poor esophageal function, reduced stomach acid, nutrient malabsorption, microbiome disruptions, and more, the effects of aging on our digestive system can significantly impact and affect the daily lives of older adults.

In this article, learn more about how aging affects the entire gastrointestinal tract, the top digestive problems older adults face, and how they can manage or prevent these disturbances with diet and lifestyle.

Map your microbiome triggers and eat without fear.

Map your microbiome triggers and eat without fear.

Although you may think that the “gut” is just the stomach and intestines, the gastrointestinal tract (GI tract) starts in the mouth, continues until the anus, and also includes accessory organs that play a role in digestion along the way, like the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas.

Let’s take a look at how aging affects each part of the digestive tract, starting with the mouth.

Digestion begins in the mouth—and one of the first noticeable effects of aging is reduced saliva production, which can cause xerostomia or dry mouth.

Dry mouth isn’t just an annoying side effect of aging—there are real health risks that can come along with it. Xerostomia is linked to difficulty swallowing food (dysphagia), elevated risk of choking, increased dental caries (cavities), periodontal disease, and impaired digestion.2

But why do we develop dry mouth as we age? Well, saliva is produced predominantly in acinar cells of the salivary glands, and research shows that the volume of acinar cell saliva secretion is reduced in older adults.1

With age, there are also reductions in salivary flow rate and the number of olfactory and taste receptors that lead to diminished neuronal salival stimulation (like when you walk by a bakery and your mouth begins to water).

One exceedingly common cause of xerostomia in older people is medication use—especially polypharmacy (taking more than one prescription medication)—which often causes dry mouth as a side effect.2

Next up is the esophagus—the muscular tube that connects the mouth to the stomach—which tends to experience reduced motility and strength with age.

We need strong esophageal contractions to move food efficiently into the stomach. Otherwise, it can take longer to swallow food entirely, leading to feelings of reflux and an increased risk of food entering the airways (a dangerous condition called aspiration).

Age also causes reduced tension in the upper esophageal sphincter (UES). This flap-like muscle prevents air from entering the esophagus while breathing and stops food from entering the pharynx while eating. Decreased UES tension with age can contribute to dysphagia and feeling like food is stuck in the throat.

The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) can also be affected, which is the muscle that allows food to pass through to the stomach but closes to prevent stomach acid from entering back into the esophagus. With poor LES tension, feelings of acid reflux (technically called gastroesophageal reflux disease or GERD) or heartburn are common.

Research has found that people over age 40 start to experience esophageal changes, including increased stiffness and reduced peristalsis (the muscle contractions that move food down the GI tract).3

The aging digestive tract is often characterized by reduced stomach acid production—a state called hypochlorhydria.

The main component of stomach or gastric acid is hydrochloric acid or HCl. We need the right amount of stomach acid to digest food (especially proteins), activate digestive enzymes, absorb nutrients, and kill off pathogens from food. Without enough acid, we can experience indigestion and an inability to eat enough food without getting too full.

The primary nutrient affected by low stomach acid production is vitamin B12, which requires gastric acid and an enzyme called pepsin to release B12 from the proteins in foods it’s bound to. Without enough acid, we can’t absorb vitamin B12 well, even if we eat plenty of it.

This, combined with the age-related decrease in another necessary protein called intrinsic factor, is a significant reason why vitamin B12 deficiency is so prevalent in older adults.4

Other changes to the stomach include a reduced ability of the stomach’s lining to resist damage, resulting in an increased risk of stomach ulcers (peptic ulcer disease), gastritis, and Helicobacter pylori infection (H.pylori).5

The aging stomach may also have reduced elasticity and a slower rate of gastric emptying into the small intestine, leading to someone not being able to eat as much food as they once could. In many elderly patients who don’t eat enough calories, this can be a serious problem.

The small intestine, where most nutrient absorption occurs, remains relatively stable in structure and function as we age. However, some gastrointestinal diseases occurring in the small intestine can increase in risk with age.

Some conditions related to the small intestine that may be seen include:

The large intestine, or colon, can experience changes like weakened muscle tone and a decreased ability of the intestinal smooth muscles to contract and relax.

This can lead to slower colonic transit time, which translates to constipation. However, some older adults have faster transit time, which could mean diarrhea.

Chronic constipation is much more common in older adults, with estimates that the rates increase from 28% in the general population to 40% in older adults and 50% of nursing home residents.5 Key risk factors for chronic constipation are medication use and polypharmacy, which often cause slow gut motility and disrupted bowel habits.

Recent research has also looked at how the gut microbiome changes with age. A loss of both microbial quantity and diversity can alter the microbiome, increasing the risk of IBS (irritable bowel syndrome), IBD (inflammatory bowel disease), and constipation.5

Another disease of the large intestine that is almost exclusively seen in older adults is diverticular disease, affecting less than 10% of people over 40, compared to 70% of people over 80 developing it.6

Diverticulosis is the presence of diverticula in the intestines—sac-like pouches on the colonic wall. While diverticulosis is harmless (generally), it can turn into diverticulitis when they become inflamed or infected. Diverticulitis can cause fever, digestive problems, and stomach pain.

Causes of diverticular disease in older adults include low intake of fiber, constipation, NSAID use, and some medications.

Lastly, colon cancer rates increase in older adults (although many younger adults are now developing it, too).

Although not in the continuous tube that runs from mouth to rectum, the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas are essential accessory organs that aid in digestion and absorption.

The liver can change significantly with age (especially with alcohol, medications, and unhealthy lifestyles), which can reduce its ability to metabolize drugs, alcohol, and other substances.

Bile production in the liver may also decrease, impacting the digestion and absorption of fats. Changes in bile composition and production can lead to gallstones, which can cause intense abdominal pain.

In the aging pancreas, you may see fewer digestive enzymes produced or pancreatic insufficiency, which leads to poor digestion and malabsorption of fats.

Ways to support digestive health with age and prevent some of these common age-related gastrointestinal conditions include:

Some foods that get harder to digest with age include dairy, high-fat foods, high-fiber foods, caffeine, alcohol, spicy foods, meat, and fried foods.

The most common digestive complaint in older adults is likely chronic constipation, which affects 40 to 50% of older adults.

Your stomach does not shrink with age, but it may have reduced elasticity and a slower gastric emptying rate into the small intestine. This could lead to someone not being able to eat as much food as they once could, which may make them think their stomach is smaller.