Save $40 on your initial consult with a TNI Dietitian!

Talk to a real Dietitian for only $99: Schedule Now

This post contains links through which we may earn a small commission should you make a purchase from a brand. This in no way affects our ability to objectively critique the products and brands we review.

Evidence Based Research To fulfill our commitment to bringing our audience accurate and insightful content, our expert writers and medical reviewers rely on carefully curated research.

Read Our Editorial Policy

What Helps the Brain and What Hurts It?

One of the best ways to help your brain health is to fuel it properly with the right foods, including those rich in antioxidants, fiber, healthy fats, and protein. The opposite is true, too—one major way to harm your brain is to eat ultra-processed, low-nutrition foods regularly.

Two recent studies from May 2024 verified this: the first showed that ultra-processed food intake was linked to an increased risk of cognitive impairment and stroke, while the second identified healthy nutrients that improved brain health with age.1,4

While a lot of people know that unhealthy foods can cause weight gain and metabolic problems, it’s lesser known that what you eat (or don’t) is also highly linked to cognitive and neurological disorders. Let’s take a closer look at what the studies found.

Although it’s kind of a no-brainer (pun intended) that eating unhealthy foods is, well, unhealthy for us, this research really drives the point home.

Published in May 2024 in Neurology, this study from Harvard Medical School followed 30,239 people age 45 or older for an average of eleven years.1

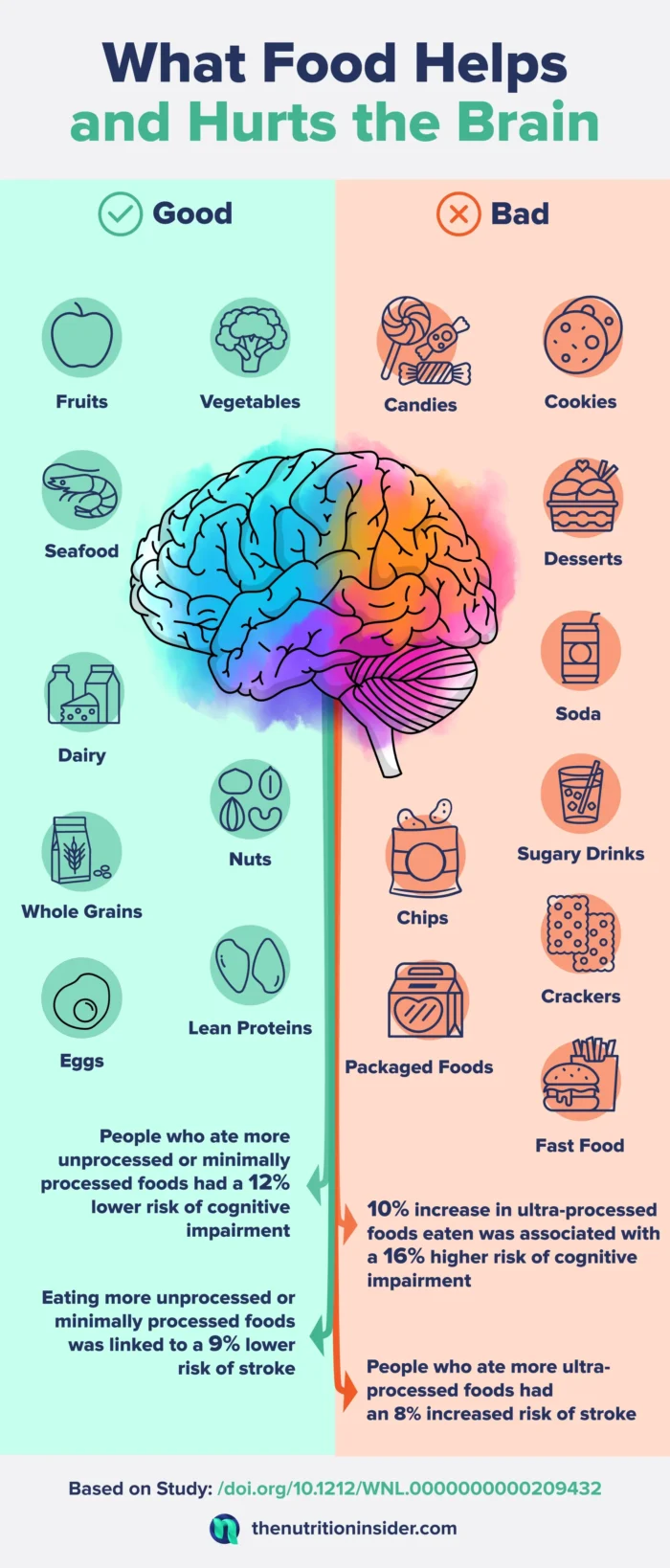

They found a 10% increase in ultra-processed foods eaten associated with a 16% higher risk of cognitive impairment. On the flip side, people who ate more unprocessed or minimally processed foods had a 12% lower risk of cognitive impairment.1

Similarly, people who ate more ultra-processed foods had an 8% increased risk of stroke, while eating more unprocessed or minimally processed foods was linked to a 9% lower risk of stroke. The effect of ultra-processed foods on stroke risk was higher among Black adults, with a 15% relative increase in the risk of stroke in this population.1

Ultra-processed foods include candy, cookies, desserts, soda, sugary drinks, most crackers and chips, fast food, and many packaged foods. Typically, ultra-processed foods are high in added sugar, saturated fat, and sodium and low in protein, micronutrients, antioxidants, and fiber. Conversely, unprocessed or minimally processed foods include meat, eggs, dairy, fruits and vegetables (even canned or frozen ones), and whole grains.

According to a 2017 definition, ultra-processed foods are:2

“Industrial formulations typically with 5 or more and usually many ingredients. Besides salt, sugar, oils, and fats, ingredients of ultra-processed foods include food substances not commonly used in culinary preparations, such as hydrolyzed protein, modified starches, hydrogenated or interesterified oils, and additives whose purpose is to imitate sensorial qualities of unprocessed or minimally processed foods and their culinary preparations or to disguise undesirable qualities of the final product, such as colorants, flavorings, nonsugar sweeteners, emulsifiers, humectants, sequestrants, and firming, bulking, de-foaming, anticaking, and glazing agents.”

While we’re on the topic, another recently published meta-analysis from June 2024 combined data from 122 studies about ultra-processed foods.3

The researchers reported that high ultra-processed food consumption was linked to an increased risk of diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, all-cause mortality, depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders.

Two other somewhat surprising health conditions were found to be significantly associated with the highest ultra-processed food (UPF) consumption: renal (kidney) function decline (25% increased risk) and wheezing in children and adolescents (42% increased risk).3

According to the authors, “At present, not a single study reported an association between UPF intake and a beneficial health outcome.” No surprise there, but it’s still a “yikes!”

Now for some good news: a second study highlighted the best foods and nutrients you can consume to improve your brain health and cognition.4

Published in the journal NPJ Aging in May 2024, researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Center for Brain, Biology, and Behavior uncovered how certain nutrients play a role in healthy brain aging.

Although this study is much smaller than the first—just 100 participants—the results were still pivotal, as it is one of the first studies to combine brain imaging, blood biomarkers, and cognitive assessments.

The researchers collected plasma nutrient biomarkers, cognitive assessments, and MRI scans from cognitively healthy adults aged 65 to 75. They then divided the adults into two groups: accelerated brain aging and slower brain aging.

The adults with slower brain aging had a distinct nutrient profile with specific nutrient biomarkers found to be higher. These included:

These nutrients that the brain needs are similar to those seen in a Mediterranean-style diet rich in fruits, vegetables, seafood, dairy, whole grains, eggs, nuts, and lean proteins.

For example, vaccenic acid is found in dairy products, EPA is found in fatty fish, vitamin E is in most nuts, and zeaxanthin is a carotenoid antioxidant in yellow-orange foods like egg yolks, mangos, and orange bell peppers. Choline is especially important for brain health, but most Americans do not get enough of it. In one study, adults who consumed more dietary choline had better verbal and visual memory test scores than those who didn’t eat as much.5 Choline is a vital component of cell membranes, leading to its involvement in cell signaling, fat transport, and neurotransmitter synthesis. The highest choline foods are egg yolks, seafood, liver, soybeans, Brussels sprouts, and broccoli.

One meal will never make or break your health—but the pattern of how you eat over the years certainly can. These new studies may seem obvious to some (eat less unhealthy foods and eat more healthy ones). Still, they help tease out the specific cognitive changes that can occur when eating a diet predominantly ultra-processed versus minimally processed foods.

To recap, the new research showed that a higher intake of ultra-processed foods increased the risk of cognitive impairment and stroke. Another meta-analysis on the same topic also found a significantly increased risk of diabetes, wheezing in kids, and renal failure from ultra-processed foods.

But it’s not all bad news! The last study showed how we can be proactive with our diets to support brain health: adults with higher blood levels of vitamin E, choline, fatty acids, and carotenoid antioxidants had slower-than-expected brain aging.