This post contains links through which we may earn a small commission should you make a purchase from a brand. This in no way affects our ability to objectively critique the products and brands we review.

What Does Fiber Do for the Body?

Evidence Based Research To fulfill our commitment to bringing our audience accurate and insightful content, our expert writers and medical reviewers rely on carefully curated research.

Read Our Editorial Policy

Fiber has been referred to as “nature’s broom,” and while this is accurate when it comes to how it “sweeps” food and waste through our intestines, fiber does much more than that.

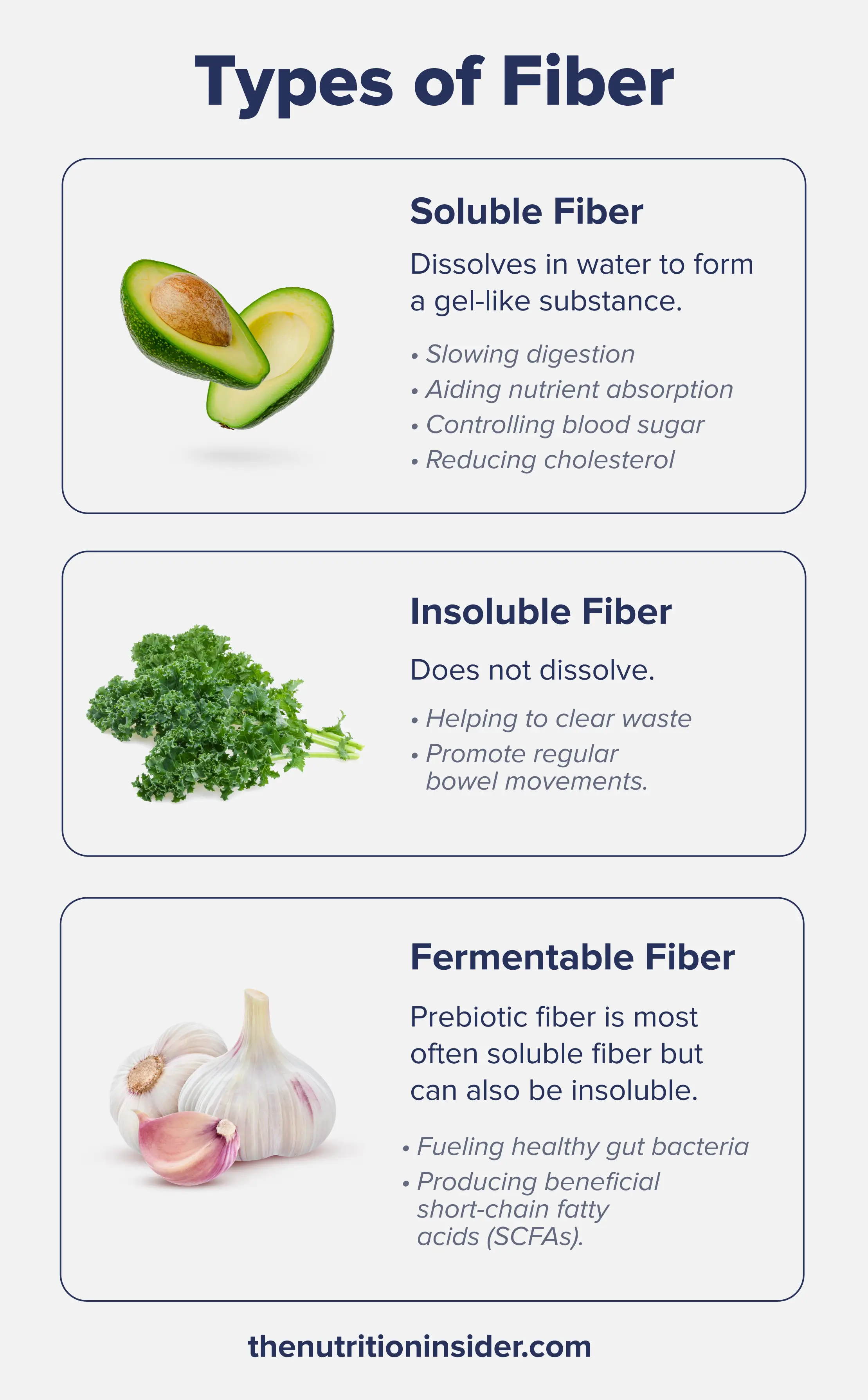

How fiber works in the body depends on its type—in this article, we’ll take a closer look at the mechanisms and benefits behind soluble, insoluble, and fermentable fibers.

What Does Fiber Do in the Body?

Fiber is a non-digestible carbohydrate found in plants. Since it is not digested or absorbed, it passes through the gastrointestinal tract intact, helping food and waste move through our system and benefiting our health. But there are differences based on the type of fiber—let’s dive in.

Soluble Fiber

As the name suggests, soluble fiber dissolves in water, forming a gel-like substance in your digestive system.

This slows down digestion, which is beneficial for helping you absorb nutrients, preventing blood glucose spikes after eating, and boosting satiety.1

Soluble fiber is also known to help lower your total blood cholesterol levels, improve blood sugar levels, and reduce insulin resistance.2

High-fiber foods that primarily contain soluble fiber include oat bran, barley, nuts, seeds, beans, lentils, peas, psyllium husk, apples, carrots, citrus fruits, avocados, pears, and berries.

Insoluble Fiber

Insoluble fiber doesn’t dissolve in water, remaining intact as it passes through your digestive system.

This helps “move things along,” clearing out waste and facilitating healthy bowel movements.1

Whole-wheat flour, wheat bran, nuts, beans, potatoes, quinoa, brown rice, legumes, kale, almonds, walnuts, and some seeds, like sesame, are foods rich in insoluble fiber.

Many foods have both soluble and insoluble fibers. For example, the peels, skins, and stems of fruits and vegetables (like apple skins, carrot peels, and broccoli stems) are primarily insoluble fiber, while the inner portions are soluble.

Fermentable (Prebiotic) Fiber

Another subtype is fermentable fiber, which is most often soluble fiber but can also be insoluble.

Prebiotic (fermentable) fibers are highly beneficial for the gut microbiome—the collection of bacteria that live in our intestinal tract—as they act as fuel for your healthy gut bacteria to consume and thrive on.

This is because prebiotic fiber consumption leads to the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

SCFAs are beneficial fermentation byproducts known as metabolites produced when our intestinal bacteria feed on prebiotic fibers, with the most common being butyrate, acetate, and propionate.

Colon cells in the gut’s epithelium (the thin layer of cells making up the gut lining) prefer butyrate as a fuel source (even more than glucose).3

Butyrate is an essential nutrient that helps colonocytes (colon cells) grow and thrive. It promotes normal colon cell growth, supports healthy mucus production, and strengthens the intestinal barrier.3

Therefore, having enough available butyrate (which comes from eating prebiotic fibers) may be a critical factor in protecting against colonic disorders.

SCFAs also lower pH in the gut, which limits the growth of harmful bacteria that cannot survive in lower-pH environments and enhance the absorption of calcium and other minerals.3

Prebiotic fiber can be found in garlic, leeks, onions, less-ripe bananas, oats, whole wheat bran, barley, chicory, asparagus, Jerusalem artichokes, and cooked-then-cooled potatoes.

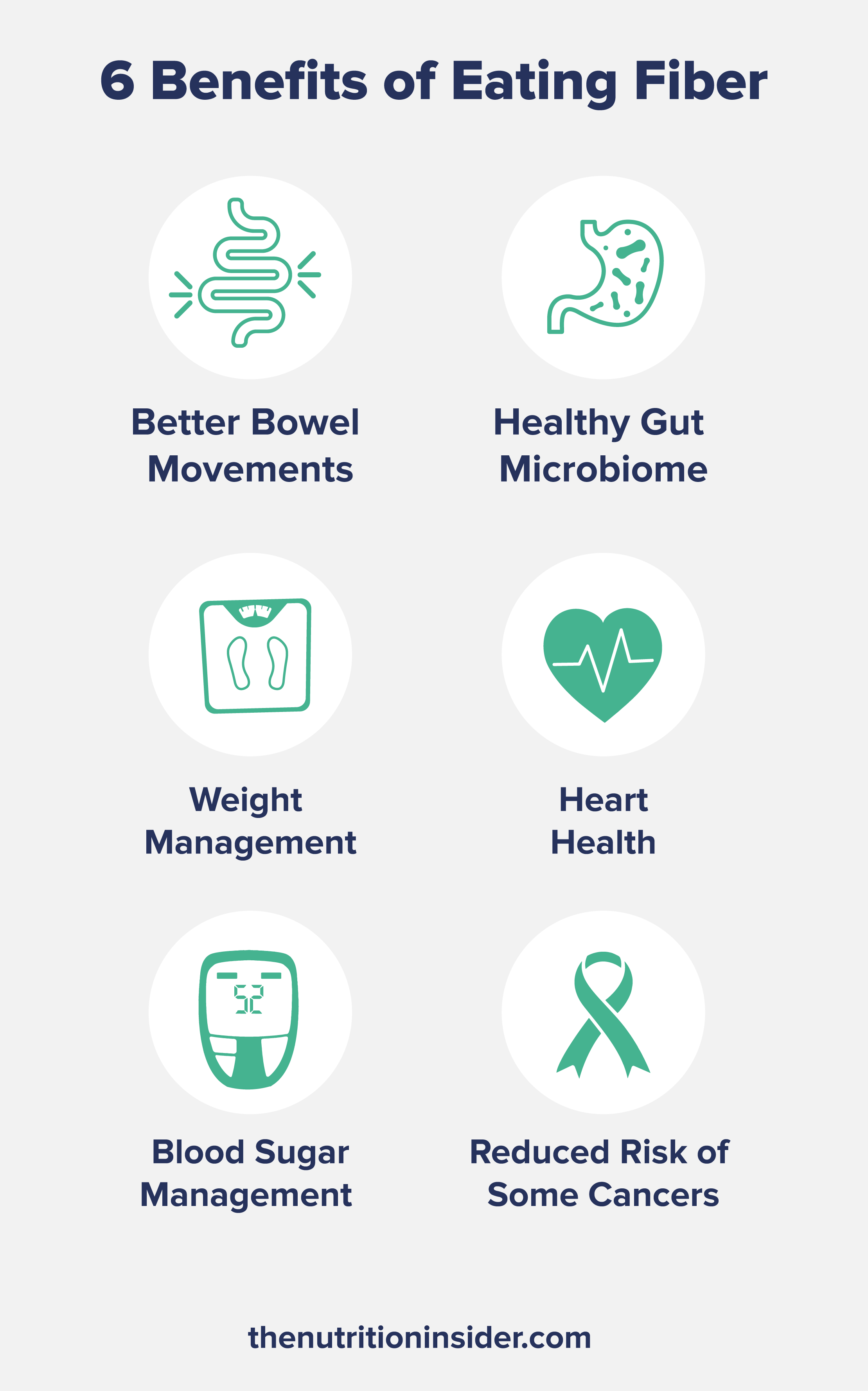

6 Benefits of Eating Fiber

1. Better Bowel Movements

The most well-known benefit of dietary fiber is its link to “regularity.” In other words, higher fiber intake promotes healthy and regular bowel movements.

As no one really loves to talk about their bowel habits (8-year-old boys excluded), this association is what gives fiber its less-than-exciting reputation.

That said, feeling constipated is no fun, and fiber can help to prevent that sluggish and uncomfortable digestion.

Soluble, insoluble, and fermentable fibers are all beneficial for improving bowel movements, including constipation and the other side of things (that even less-fun word, diarrhea).

While soluble fiber softens stool due to its gel-like substance, insoluble fiber adds bulk and acts as a bowel broom, sweeping waste out. Essentially, you need both types of fiber to make large but soft stools that pass easily.

Psyllium husk (soluble fiber) and inulin (prebiotic fiber) may be particularly useful for helping with constipation. In a 2020 review paper, researchers found that psyllium was 3.4 times more effective than insoluble wheat bran for increasing stool output, as well as softening stool.4

A different 2020 review found that inulin fiber increased the frequency of bowel movements and improved stool consistency in people with IBS-C (irritable bowel syndrome with constipation).5

However, consuming too much fiber (especially in supplemental form) can actually worsen digestive issues, so it’s ideal to stick to recommended daily amounts.

2. Healthy Gut Microbiome

Prebiotic fiber is the main type that benefits your gut microbiome. When we eat prebiotic fibers, our gut bacteria ferment them and break them down, producing short-chain fatty acids.

Essentially, the more SCFAs your gut has, the healthier your gut microbiome. This is because healthy gut bacteria thrive on SCFAs, and SCFAs also reduce the pH of the intestines, which reduces the viability of some pathogenic bacteria.3

A review paper published in the journal Microorganisms concluded that people eating fiber-rich diets—especially whole grains and vegetables—have dramatically different microbiomes and greater microbial diversity than those consuming less fiber.6

In a small study, healthy adults who ate an inulin-rich diet (including Jerusalem artichokes, leeks, shallots, garlic, celery root, and onions) for two weeks had substantial changes to their gut microbiomes.7 Their beneficial Bifidobacterium longum levels increased by threefold, while the disease-associated Clostridia were reduced. Three weeks later, these changes were reversed, indicating that consistent fiber intake is necessary to maintain healthy gut microbiota.7

3. Weight Management

People who eat higher fiber diets tend to have healthier body weights. One reason is that fiber is satiating, meaning you get more full eating fiber-rich foods, which can reduce overall calorie intake.

Another potential reason is that people with healthier body weights tend to have specific beneficial gut bacteria, which fiber can help to modulate.8

Research from 2023 looked at data from over 4,400 people on a 16-week plant-forward, fiber-rich diet, finding that people who ate the most fiber lost the most weight. Compared to the people who gained weight or stayed the same, those who lost weight increased their daily intake of high-fiber foods by 2.8 servings—especially fruits, vegetables, and beans—totaling 9.1 servings of fiber-rich food daily.9

Fiber supplements may also help. One small study with 48 overweight adults found that taking 21 grams of fructooligosaccharide prebiotics for 12 weeks led to significant weight loss compared to a control group.10

4. Heart Health

Higher fiber intake has been shown to improve heart health, including reducing the risk of cardiovascular diseases.

One observational study of almost 2,300 adults found that people in the highest fiber intake group had a 61% reduced risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) compared to people in the lowest intake group.11

Soluble fiber intake had an even more substantial benefit, with the top soluble fiber eaters having an impressive 81% reduction in CVD risk compared to the lowest group.11

One mechanism behind this benefit is that soluble fiber reduces lipid uptake from the digestive tract, leading to lower levels of unhealthy LDL cholesterol.12

Soluble fiber also has been shown to reduce blood pressure, inflammatory markers, and blood glucose, which are all markers of cardiovascular health.12

5. Blood Sugar Management

Fiber also benefits blood sugar management, which is a key component of metabolic health and may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes.13

This is because the non-digestible fiber, which is always paired with carbohydrates in foods, slows down the rate of glucose absorption and blunts blood sugar and insulin spikes.13

A meta-analysis of 16 other meta-analyses concluded that higher fiber intake significantly reduced the risk of type 2 diabetes by 15 to 19%, with the greatest benefit coming from consuming cereal fibers like oats and barley. Compared to those consuming the fewest cereal fibers, people who ate the highest amount had up to a 33% reduced risk of type 2 diabetes.14

Fiber supplements have also been found to help with blood sugar management.

In a randomized controlled trial, women with type 2 diabetes were randomized to take inulin and oligofructose fibers or a placebo for eight weeks. Those in the prebiotic fiber group experienced decreased fasting blood sugar and hemoglobin A1C (a standard diagnostic marker for type 2 diabetes or prediabetes).15

6. Reduced Risk of Some Cancers

Eating enough fiber may reduce the risk of some cancers, especially colon, rectal, and colorectal cancers.

A 2022 meta-analysis concluded that both soluble and insoluble fiber are protective against colorectal cancer, reducing the risk by up to 23%.16

Fiber is thought to reduce cancer risk in the intestines and colon because it increases stool transit time and quickly eliminates potentially carcinogenic compounds, harmful metabolites, and toxic waste.16

Short-chain fatty acids also play a role here. Butyrate helps to maintain colonocyte health in the intestines and reduces the chances of tumor growth.

In lab studies, butyrate has been shown to induce apoptosis (programmed cell death) of colon cancer cells and exhibit anti-tumor activity, including inhibiting colorectal cancer cell proliferation.17,18

Fiber may also reduce the risk of breast cancer. A meta-analysis of 20 studies found that total fiber consumption was associated with an 8% lower risk of breast cancer, with soluble fiber having a greater benefit than insoluble fiber (although both were still beneficial).19

The link between fiber and breast cancer also involves faster elimination. Fiber-rich foods increase stool transit time, which reduces estrogen reabsorption in the colon and enhances its excretion in the stool. As high circulating estrogen levels are associated with breast cancer development, this may be one reason why fiber reduces the risk.20

Fiber FAQs

Can fiber help you lose weight?

Yes, eating more fiber is thought to help maintain a healthy body weight or lose weight. Fiber from foods is likely better, but some fiber supplements have been shown to help, as well. Soluble and fermentable fibers are the most likely types to help with weight loss.

Does fiber cancel out carbs?

While fiber does not technically “cancel out” carbohydrates, it does reduce their glycemic impact. Fiber slows down the rate of glucose absorption, blunting blood sugar and insulin spikes. Because we don’t digest fibrous carbohydrates, they don’t count towards your daily carb intake, which is referred to as “net carbs.” On a nutrition label, you can subtract the grams of fiber from the total grams of carbohydrates to get net carbs.

Does fiber give you energy?

As we don’t digest and absorb fiber, it doesn’t provide us with energy in the same sense that sugars, fats, or proteins do. However, fiber may help us feel more energized because it boosts nutrient absorption and satiety. As many people feel low energy when they are hungry or not eating enough nutrients, fiber may help here.

Does fiber clean your bowels?

As fiber has been described as “nature’s broom,” you could say that fiber cleans your bowels. Both soluble and insoluble fiber are helpful for healthy bowel movements, as soluble fiber softens stool with its gel-like substance, and insoluble fiber adds bulk that sweeps unwanted food and waste along.

- Barber, T. M., Kabisch, S., Pfeiffer, A. F. H., & Weickert, M. O. (2020). The Health Benefits of Dietary Fibre. Nutrients, 12(10), 3209. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103209

- Erkkilä, A. T., & Lichtenstein, A. H. (2006). Fiber and cardiovascular disease risk: how strong is the evidence?. The Journal of cardiovascular nursing, 21(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005082-200601000-00003

- Blaak, E. E., Canfora, E. E., Theis, S., Frost, G., Groen, A. K., Mithieux, G., Nauta, A., Scott, K., Stahl, B., van Harsselaar, J., van Tol, R., Vaughan, E. E., & Verbeke, K. (2020). Short chain fatty acids in human gut and metabolic health. Beneficial microbes, 11(5), 411–455. https://doi.org/10.3920/BM2020.0057

- McRorie, J. W., Jr, Fahey, G. C., Jr, Gibb, R. D., & Chey, W. D. (2020). Laxative effects of wheat bran and psyllium: Resolving enduring misconceptions about fiber in treatment guidelines for chronic idiopathic constipation. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 32(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000346

- Bărboi, O. B., Ciortescu, I., Chirilă, I., Anton, C., & Drug, V. (2020). Effect of inulin in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (Review). Experimental and therapeutic medicine, 20(6), 185. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2020.9315

- Fu, J., Zheng, Y., Gao, Y., & Xu, W. (2022). Dietary Fiber Intake and Gut Microbiota in Human Health. Microorganisms, 10(12), 2507. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10122507

- Hiel, S., Bindels, L. B., Pachikian, B. D., Kalala, G., Broers, V., Zamariola, G., Chang, B. P. I., Kambashi, B., Rodriguez, J., Cani, P. D., Neyrinck, A. M., Thissen, J. P., Luminet, O., Bindelle, J., & Delzenne, N. M. (2019). Effects of a diet based on inulin-rich vegetables on gut health and nutritional behavior in healthy humans. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 109(6), 1683–1695. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqz001

- Noor, J., Chaudhry, A., Batool, S., Noor, R., & Fatima, G. (2023). Exploring the Impact of the Gut Microbiome on Obesity and Weight Loss: A Review Article. Cureus, 15(6), e40948. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.40948

- Kelly, R. K., Calhoun, J., Hanus, A., Payne-Foster, P., Stout, R., & Sherman, B. W. (2023). Increased dietary fiber is associated with weight loss among Full Plate Living program participants. Frontiers in nutrition, 10, 1110748. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1110748

- Parnell, J. A., & Reimer, R. A. (2009). Weight loss during oligofructose supplementation is associated with decreased ghrelin and increased peptide YY in overweight and obese adults. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 89(6), 1751–1759. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.27465

- Mirmiran, P., Bahadoran, Z., Khalili Moghadam, S., Zadeh Vakili, A., & Azizi, F. (2016). A Prospective Study of Different Types of Dietary Fiber and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Nutrients, 8(11), 686. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8110686

- Soliman G. A. (2019). Dietary Fiber, Atherosclerosis, and Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients, 11(5), 1155. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11051155

- Giuntini, E. B., Sardá, F. A. H., & de Menezes, E. W. (2022). The Effects of Soluble Dietary Fibers on Glycemic Response: An Overview and Futures Perspectives. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 11(23), 3934. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11233934

- McRae M. P. (2018). Dietary Fiber Intake and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses. Journal of chiropractic medicine, 17(1), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2017.11.002

- Aliasgharzadeh, A., Khalili, M., Mirtaheri, E., Pourghassem Gargari, B., Tavakoli, F., Abbasalizad Farhangi, M., Babaei, H., & Dehghan, P. (2015). A Combination of Prebiotic Inulin and Oligofructose Improve Some of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Women with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Advanced pharmaceutical bulletin, 5(4), 507–514. https://doi.org/10.15171/apb.2015.069

- Arayici, M. E., Mert-Ozupek, N., Yalcin, F., Basbinar, Y., & Ellidokuz, H. (2022). Soluble and Insoluble Dietary Fiber Consumption and Colorectal Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrition and cancer, 74(7), 2412–2425. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2021.2008990

- Bordonaro M. (2020). Further analysis of p300 in mediating effects of Butyrate in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Journal of Cancer, 11(20), 5861–5866. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.47160

- Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K., Marano, L., Merola, E., Roviello, F., & Połom, K. (2022). Sodium butyrate in both prevention and supportive treatment of colorectal cancer. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 12, 1023806. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.1023806

- Farvid, M. S., Spence, N. D., Holmes, M. D., & Barnett, J. B. (2020). Fiber consumption and breast cancer incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer, 126(13), 3061–3075. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32816

- Gaskins, A. J., Mumford, S. L., Zhang, C., Wactawski-Wende, J., Hovey, K. M., Whitcomb, B. W., Howards, P. P., Perkins, N. J., Yeung, E., Schisterman, E. F., & BioCycle Study Group (2009). Effect of daily fiber intake on reproductive function: the BioCycle Study. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 90(4), 1061–1069. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.27990