This post contains links through which we may earn a small commission should you make a purchase from a brand. This in no way affects our ability to objectively critique the products and brands we review.

Can You Reverse Alcohol Damage?

Evidence Based Research To fulfill our commitment to bringing our audience accurate and insightful content, our expert writers and medical reviewers rely on carefully curated research.

Read Our Editorial Policy

Chronic alcohol consumption can lead to many severe health issues, even if you don’t have alcohol use disorder (an updated term for alcohol addiction).

According to the World Health Organization, no amount of alcohol is considered safe for our health. However, it’s incredibly common to drink alcohol—and not to stop at just one drink.1

If you’ve had a past—or present—of partying and binging, you may be concerned about the potential damage you may have incurred from drinking. Fortunately, we’re here to give you some good news: in many cases, you can reverse (most of) the damage from alcohol if you stop drinking.

Although it doesn’t apply to everybody or more severe cases, several health conditions or symptoms can improve after quitting alcohol—let’s take a closer look.

A very important disclaimer: If you are dependent on alcohol or think you might have an alcohol use disorder, do not attempt to stop drinking alcohol on your own. It’s dangerous to quit alcohol cold turkey without medical supervision, as severe alcohol withdrawal symptoms can occur and be life-threatening. Please call the SAMHSA National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357) if you need help with mental health services, alcohol abuse, or substance abuse.

Can You Reverse Alcohol Damage?

Chronic alcohol consumption—even moderate yet habitual drinking—can damage just about every one of our organs and systems, including the liver, heart, brain, skin, gut, and immune system.

But is this damage irreversible, or do we have a chance to repair it?

As we’ll get into, research shows that a lot of alcohol-induced damage can be repaired. Of course, the first and most essential step to fully reversing alcohol damage is to stop drinking. Otherwise, any attempt with supplements, healthy eating, or lifestyle changes will negate your progress and cause further damage if you’re still drinking.

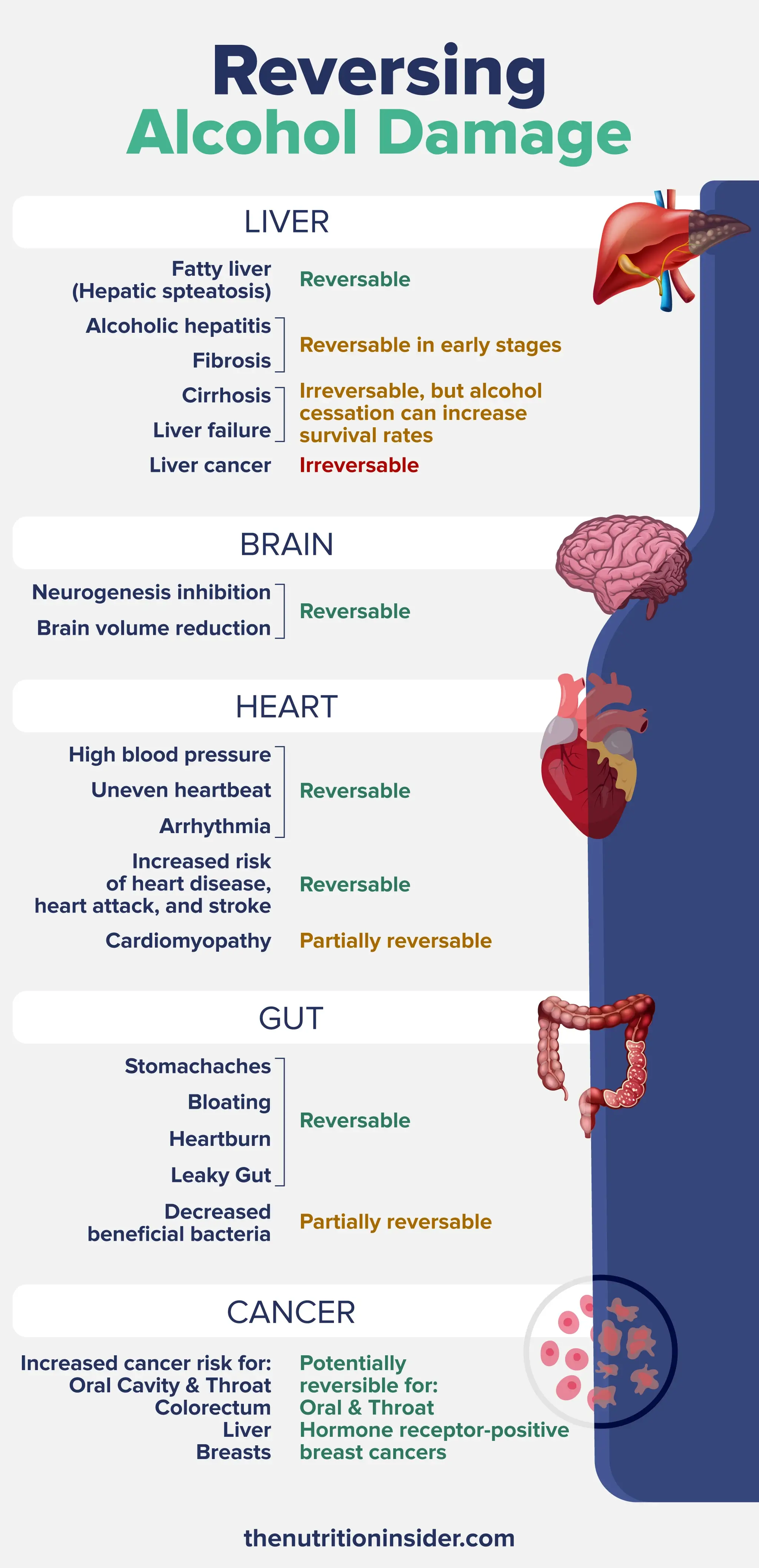

Reversing Alcohol Damage in the Liver

As the liver filters alcohol and metabolizes it, it is the organ most directly affected by alcohol consumption—and, fortunately, it’s the organ most able to repair itself from the damage.

According to a review paper published in the journal Alcohol Research, “Even after years of heavy alcohol use, the liver has a remarkable regenerative capacity and, following alcohol removal, can recover a significant portion of its original mass and function.”2

This is great news, as chronic alcohol use can lead to many liver conditions, including fatty liver, alcoholic hepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, liver failure, and liver cancer.

The first three conditions on that list—fatty liver, alcoholic hepatitis, and fibrosis—can be reversed if the case is not too severe.2

Alcoholic fatty liver disease (also known as hepatic steatosis) is the first stage of alcohol-related liver disease, and that is the easiest to turn around. Research shows that after just 2 to 3 weeks of alcohol abstinence, fatty liver completely resolves.2

Milder cases of alcoholic hepatitis (high levels of inflammation in the liver) and early stages of fibrosis (a buildup of scar tissue from the liver trying to repair itself after damage and inflammation) can also be reversed, but severe conditions of fibrosis cannot.3

Unfortunately, if you have progressed to cirrhosis—a late stage of liver disease where healthy liver tissue is replaced by scar tissue, and liver cells die or stop functioning—or liver failure, these stages are not reversible, even if you stop drinking. However, stopping drinking alcohol immediately can significantly increase survival rates in people with both early and late stages of cirrhosis or liver failure.4

Reversing Alcohol Damage in the Brain

Alcohol consumption can interfere with healthy neurotransmitter activity and change or damage neurons, which can lead to short- and long-term consequences to cognitive function.5

Research has shown that chronic drinkers have smaller brain volumes than non-drinkers—but can this “lost” brain grow back? Some studies say yes, it can.

Neurogenesis—the formation of new neurons—is now known to occur in adults, but alcohol intoxication has been shown to inhibit this process. Therefore, quitting drinking should allow for neurogenesis to take place again.6

This was seen in animal models, where abstaining from alcohol resulted in the growth of new neural stem cells and the formation of new neurons, which is indicative of brain growth.6

Another study shows that people with alcohol use disorder who reduce their alcohol intake or stop drinking permanently have a greater brain volume than people who continue to drink heavily. The brain regions affected are involved with decision-making, emotional regulation, and working memory.7

Notably, people in this study who reduced their alcohol intake to “low-risk drinking”—less than 1.5 drinks per day for women and less than 3 for men—had comparable brain volumes to non-drinkers.

If brain cells die, they cannot grow back. However, if a cell has only shrunk from alcohol consumption, it can return to normal volume once alcohol is removed. Similarly, new neurons can be formed via neurogenesis, which can be further facilitated by aerobic exercise, brain training games, quality sleep, and a healthy diet rich in polyphenolic antioxidants.8

Reversing Alcohol Damage in the Heart

Chronic or excessive alcohol consumption can impact many areas of the cardiovascular system, including high blood pressure, cardiomyopathy (stiffened, enlarged, or hardened heart muscles), arrhythmia, uneven heartbeat, and increasing risk of heart disease, heart attack, and stroke.

Many of these symptoms or conditions are reversed pretty quickly upon stopping drinking alcohol—especially high blood pressure and heart palpitations or arrhythmias.

One interesting study had otherwise healthy drinkers abstain from alcohol for one month. Compared to a control group that continued drinking, the abstainers saw significant reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, body weight, and insulin resistance. They also had reductions in VEGF and EGF—two key growth factors involved in cancer progression.9

In just one month of not drinking, blood pressure was reduced from an average of 136/89 mmHg to 125/82 mmHg. While that may not seem like a huge difference, it is pretty remarkable for one month. Plus, research has shown that even a 5 mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure (the top number) drops cardiovascular disease risk by 10%.10

Another study found that people with alcohol use disorder and cardiomyopathy who abstained from alcohol completely had significantly increased left ventricular function, indicating how well the heart pumps blood. Notably, people who couldn’t abstain but cut back on alcohol had almost the same improvements.11

Reversing Alcohol Damage in the Gut

Several aspects of gut health are affected by alcohol consumption. You may know this firsthand after experiencing abdominal pain or acid reflux after a night of heavy drinking.

Alcohol can irritate your digestive tract’s mucus membranes, trigger excess acid production in your stomach, and interfere with nutrient absorption. This elevated acidic state can cause reflux and acute stomach pain, as well as chronic conditions such as peptic ulcers and gastritis.

Alcohol also kills beneficial bacteria in your gut, leading to gut dysbiosis, and increases gut inflammation and intestinal hyperpermeability. This is also known as leaky gut, a condition where the intestinal lining has “leaks” that allow harmful bacteria and toxins into the bloodstream.12

The gut can recover pretty quickly once alcohol is taken out of the equation. One study found that just three weeks after people with alcohol use disorder removed alcohol, their gut barrier function was completely recovered, indicating that leaky gut was no longer present.13

However, while the abstainers had increased beneficial bacteria in their guts, the microbiomes were not entirely restored, suggesting that it takes longer than three weeks to reverse microbial damage.

Other symptoms, like stomachaches, bloating, and heartburn, may resolve in as little as a few days to a couple of weeks after quitting alcohol.

Reversing Cancer Risk Related to Alcohol Damage

Although it’s not an organ, many people are concerned about their increased cancer risk from years of drinking alcohol—and rightfully so, as alcohol is a direct cause of cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, colorectum, liver, and breast.

A comprehensive study published in the New England Journal of Medicine concluded that stopping drinking can decrease cancer-related changes to DNA within a few months to several years.14

They also found that quitting alcohol can reduce cancer risks, primarily for oral, esophageal, and hormone receptor-positive breast cancers.

For example, their analysis showed that stopping drinking for 4 years reduced the risk of oral cancer by 19%, while 5 to 9 years of cessation lowered it by 23%. Over 20 years of abstinence from alcohol reduced the risk of oral cancer by 55%, reaching the level of never-drinkers.14

Although 20 years of alcohol cessation probably sounds daunting, it’s hopeful to know that it is possible to reduce your risk of some cancers to the same extent as people who never drank.

Alcohol Damage FAQs

How long does it take for alcohol to cause irreversible damage?

It depends. Most serious health conditions, like liver cirrhosis, cancer, or alcohol-related brain damage, take 10 to 20 years of heavy drinking to develop. However, other symptoms that lead up to these conditions can develop in as little as a year of hard drinking, like heart arrhythmias or irregularities, high blood pressure, alcoholic fatty liver disease, and digestive problems. Fortunately, these symptoms are reversible.

What does 20 years of drinking do to your body?

Twenty years of drinking excessively may lead to cancer, alcoholic liver disease (including cirrhosis and advanced liver damage), brain damage, dementia, heart disease, kidney failure, ulcers, or gastritis.

How long does it take for inflammation from alcohol to go away?

This depends on how long or how excessively you’ve been drinking. If it was just a weekend of binge drinking, inflammation (both internal and external) should dissipate within 1 to 3 days. However, for chronic heavy alcohol users, internal inflammation in your organs could take several weeks to go away once you stop drinking. External inflammation, like face puffiness or bloat, could go away sooner.

- World Health Organization. (2023). No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health. https://www.who.int/azerbaijan/news/item/04-01-2023-no-level-of-alcohol-consumption-is-safe-for-our-health

- Thomes, P. G., Rasineni, K., Saraswathi, V., Kharbanda, K. K., Clemens, D. L., Sweeney, S. A., Kubik, J. L., Donohue, T. M., Jr, & Casey, C. A. (2021). Natural Recovery by the Liver and Other Organs after Chronic Alcohol Use. Alcohol research : current reviews, 41(1), 05. https://doi.org/10.35946/arcr.v41.1.05

- Ismail, M. H., & Pinzani, M. (2009). Reversal of liver fibrosis. Saudi journal of gastroenterology : official journal of the Saudi Gastroenterology Association, 15(1), 72–79. https://doi.org/10.4103/1319-3767.45072

- Lackner, C., Spindelboeck, W., Haybaeck, J., Douschan, P., Rainer, F., Terracciano, L., Haas, J., Berghold, A., Bataller, R., & Stauber, R. E. (2017). Histological parameters and alcohol abstinence determine long-term prognosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Journal of hepatology, 66(3), 610–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.11.011

- Tateno, M., & Saito, T. (2008). Biological studies on alcohol-induced neuronal damage. Psychiatry investigation, 5(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2008.5.1.21

- Crews F. T. (2008). Alcohol-related neurodegeneration and recovery: mechanisms from animal models. Alcohol research & health : the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 31(4), 377–388.

- May, A. C., Meyerhoff, D. J., & Durazzo, T. C. (2023). Non-abstinent recovery in alcohol use disorder is associated with greater regional cortical volumes than heavy drinking. Alcohol, clinical & experimental research, 47(10), 1850–1858. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.15169

- Solan, M. (2021). The book of neurogenesis: Harvard Health. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/the-book-of-neurogenesis

- Mehta, G., Macdonald, S., Cronberg, A., Rosselli, M., Khera-Butler, T., Sumpter, C., Al-Khatib, S., Jain, A., Maurice, J., Charalambous, C., Gander, A., Ju, C., Hakan, T., Sherwood, R., Nair, D., Jalan, R., & Moore, K. P. (2018). Short-term abstinence from alcohol and changes in cardiovascular risk factors, liver function tests and cancer-related growth factors: a prospective observational study. BMJ open, 8(5), e020673. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020673

- Jones, L. (2021). Lowering blood pressure is even more beneficial than previously though. British Health Foundation. https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/news-from-the-bhf/news-archive/2021/april/lowering-blood-pressure-is-even-more-beneficial-than-previously-thought

- Nicolás, J. M., Fernández-Solà, J., Estruch, R., Paré, J. C., Sacanella, E., Urbano-Márquez, A., & Rubin, E. (2002). The effect of controlled drinking in alcoholic cardiomyopathy. Annals of internal medicine, 136(3), 192–200. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00007

- Engen, P. A., Green, S. J., Voigt, R. M., Forsyth, C. B., & Keshavarzian, A. (2015). The Gastrointestinal Microbiome: Alcohol Effects on the Composition of Intestinal Microbiota. Alcohol research : current reviews, 37(2), 223–236.

- Leclercq, S., Matamoros, S., Cani, P. D., Neyrinck, A. M., Jamar, F., Stärkel, P., Windey, K., Tremaroli, V., Bäckhed, F., Verbeke, K., de Timary, P., & Delzenne, N. M. (2014). Intestinal permeability, gut-bacterial dysbiosis, and behavioral markers of alcohol-dependence severity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(42), E4485–E4493. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1415174111

- Gapstur, S. M., Bouvard, V., Nethan, S. T., Freudenheim, J. L., Abnet, C. C., English, D. R., Rehm, J., Balbo, S., Buykx, P., Crabb, D., Conway, D. I., Islami, F., Lachenmeier, D. W., McGlynn, K. A., Salaspuro, M., Sawada, N., Terry, M. B., Toporcov, T., & Lauby-Secretan, B. (2023). The IARC Perspective on Alcohol Reduction or Cessation and Cancer Risk. The New England journal of medicine, 389(26), 2486–2494. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr2306723