Save $40 on your initial consult with a TNI Dietitian!

Talk to a real Dietitian for only $99: Schedule Now

This post contains links through which we may earn a small commission should you make a purchase from a brand. This in no way affects our ability to objectively critique the products and brands we review.

Evidence Based Research To fulfill our commitment to bringing our audience accurate and insightful content, our expert writers and medical reviewers rely on carefully curated research.

Read Our Editorial Policy

Performing over 500 critical functions, our livers are incredibly hard-working organs that diligently neutralize and eliminate toxins we expose our bodies to—like alcohol.

Although it tries its very best to deal with these toxins, excess alcohol consumption will eventually take its toll on the liver. From fatty liver to fibrosis to cirrhosis, chronic and heavy drinking can seriously damage this vital organ.

In this article, we’ll go over how exactly we break down alcohol, why the liver is so affected, and the potential alcohol-related liver disease that can develop. But it’s not all doom and gloom—we’ll also talk about how to reverse liver damage from drinking alcohol.

Several enzymes, nutrients, and pathways are involved in the complex process of alcohol (ethanol) metabolism in the liver.

But before alcohol gets to the liver, it’s absorbed through the stomach and intestines. Over 90% of absorbed alcohol circulates through the bloodstream (the other ~10% is excreted via breath, sweat, or urine) before getting transported to the liver through the portal vein.

As alcohol is a toxin, the body needs to metabolize and eliminate it immediately, using enzymes that break apart the ethanol molecule into intermediary compounds that can more easily be processed and excreted. However, some of these intermediary molecules are just as toxic as alcohol.

The primary pathway for metabolizing alcohol uses the enzymes alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH).1

Alcohol is first oxidized to a compound called acetaldehyde by ADH. As acetaldehyde is a very toxic and carcinogenic molecule, the enzyme ALDH then rapidly converts acetaldehyde into acetate (acetic acid). From there, acetate is metabolized into carbon dioxide, fatty acids, and water, which can be easily excreted from the liver and eliminated.1

In addition to ADH, the enzymes cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) and catalase also break down alcohol to acetaldehyde.1

Excessive alcohol consumption increases the activity of CYP2E1, which promotes acetaldehyde production and forms reactive oxygen species (ROS)—harmful compounds also known as free radicals that damage liver cells and DNA.1

This elevation of ROS is a leading contributor to alcohol-related liver diseases, as they cause lipid (fat) accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis (scarring) in the liver.1

Other lesser-used pathways remove alcohol by combining with fatty acids to form compounds called fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs), which can also harm the liver.1

Genetics can play a significant role in how well—or poorly—your body metabolizes alcohol, which alters your risk for alcohol-related liver disease.

The enzymes ADH and ALDH have different variants or alleles that influence how quickly you convert and metabolize alcohol, as well as your risk for alcohol use disorder (an updated term for alcoholism) or liver diseases.2

Two alleles called ADH1B and ADH1C encode for more active ADH enzymes, allowing you to metabolize alcohol more quickly. These alleles are more protective against developing alcohol use disorder or alcohol-related liver disease, as ethanol will be in the body for a shorter amount of time.3

Other genetic changes are seen in many Asian populations. Up to 50% of Japanese, Chinese, and Taiwanese people have a genetic variant in ALDH called ALDH2*2, causing reduced ALDH activity.

ALDH is the enzyme that converts the toxic acetaldehyde into acetate. Without enough ALDH, people have an acetaldehyde buildup after drinking alcohol, leading to symptoms like flushing, nausea, headaches, rapid heartbeat, and dizziness.2

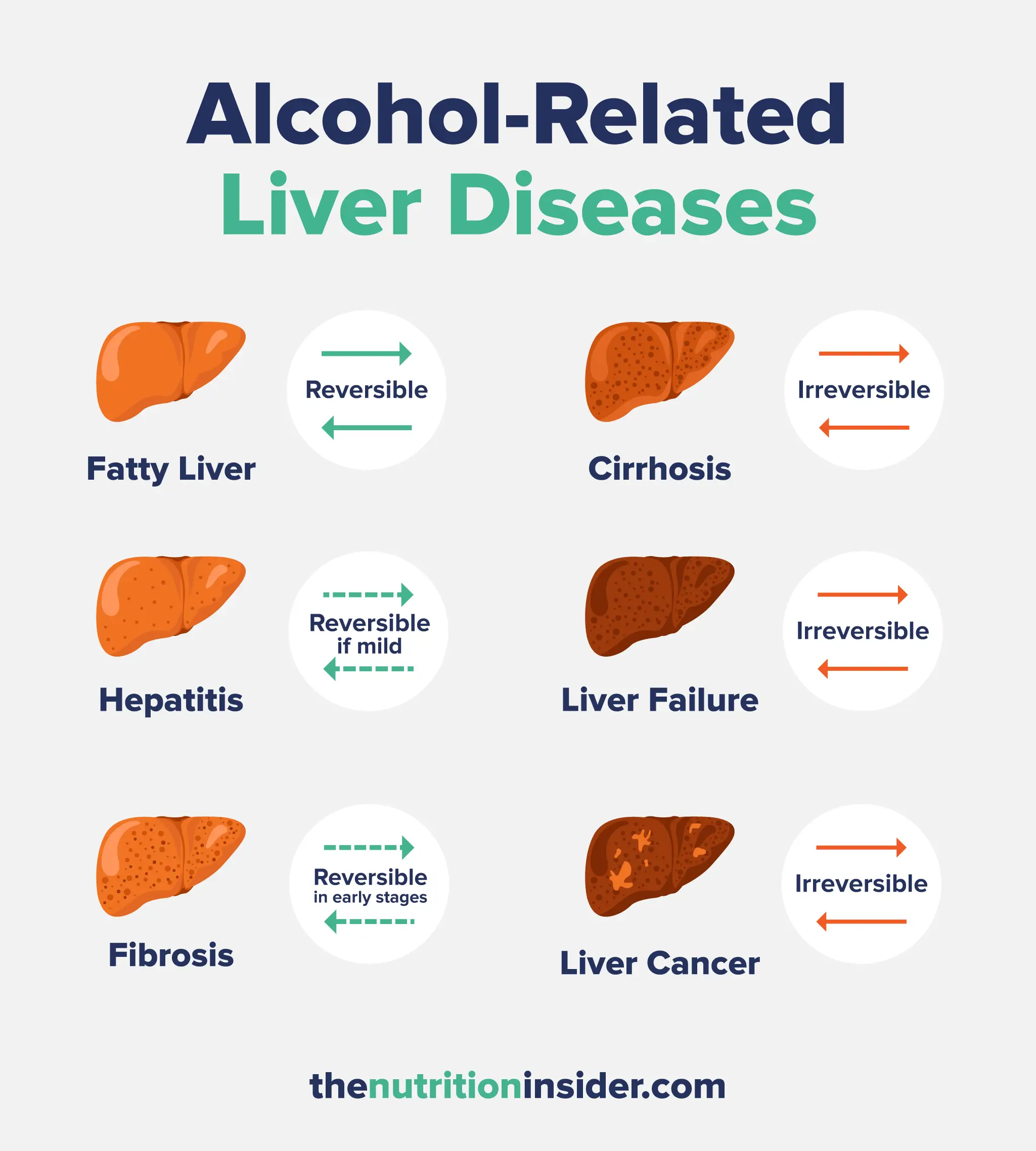

There are several stages of alcohol-associated liver disease, with some being relatively benign and reversible.

Although ethanol itself is a toxic compound and carcinogen, the majority of liver damage and disease progression occurs from the byproducts and metabolites created during alcohol metabolism—namely, acetaldehyde.

As mentioned, acetaldehyde is created after alcohol consumption, increasing ROS production and oxidative stress. Acetaldehyde also interacts directly with DNA and causes mutations and damage to chromosomes.1

Let’s take a closer look at how alcohol and its metabolic byproducts can lead to liver diseases.

Fatty liver, or hepatic steatosis, is the very common first stage of alcohol-induced liver damage, involving lipid (fat) accumulation inside liver cells. It can occur in as little as two weeks of heavy drinking of more than 60 grams of alcohol per day (about six drinks)—but it also resolves just as fast after stopping drinking.

One way that alcohol causes fatty liver is because it inhibits fatty acid oxidation—the breakdown of fat—which means it can accumulate in the liver.4 This is also one reason why alcohol can lead to body fat gain.

Alcohol also activates proteins called “sterol regulatory element binding proteins,” which induce enzymes involved with lipogenesis—the creation of fat cells.4

This condition is mostly asymptomatic, but some people feel pain in their liver region (upper right area of the abdomen, below the ribs), weakness, or nausea as it progresses.

Liver enzymes will almost certainly be elevated in this state as well, with ALT, AST, and GGT being the most commonly assessed. While elevated liver enzymes can be used to evaluate liver function, imaging tests like ultrasounds or MRIs are needed to diagnose steatosis.

Fortunately, hepatic steatosis can be completely resolved after 2 to 3 weeks of alcohol abstinence.5

The next step of liver damage is hepatitis, meaning inflammation of the liver.

Alcohol-related hepatitis is often called alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH), meaning a combination of alcoholic liver inflammation and fat accumulation. If excessive drinking continues, approximately 20% to 40% of people with fatty liver will develop ASH.5

In addition to inflammation and fatty liver, ASH is characterized by ballooning hepatocytes—a state when liver cells are injured and become rounded and enlarged, up to double their normal size.5

The liver gets inflamed from alcohol intake because the metabolization and elimination of alcohol (or any toxic substance) activate a minor immune response, which involves inflammation. In a person who does not drink regularly, the liver can resolve the inflammation. In someone drinking excessively, the inflammation will remain chronically elevated.

Depending on the severity of this stage, symptoms can range from relatively minor, like nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and weakness, to severe symptoms like jaundice, kidney failure, and confusion.

If the hepatitis case is not too severe—which would be determined by liver biopsies, liver enzyme tests, and ultrasounds—this stage can also be reversed by abstaining from alcohol.

Nutritional supplementation can also aid in recovery from alcoholic hepatitis, including higher protein and calorie intake if malnourished or sarcopenic (muscle wasting) and supplementation with zinc, vitamin D, magnesium, and B complex vitamins.6,7

After lipid accumulation and inflammation are present, the next potential stage of alcoholic liver disease is fibrosis—a buildup of fibrous scar tissue in the liver.

When the liver is damaged, liver and immune cells send messages for repair cells to travel to the injured site and help heal it.

The repair cells release collagen to help heal the injury by hardening the tissue around liver cells and protecting them from further damage.

Essentially, fibrosis occurs when fibrotic scar tissue replaces normal liver cells. Like hepatitis, less severe stages of fibrosis can be reversed. Some research even indicates that later-stage fibrosis is reversible.8 Fibrosis restricts blood flow, so doctors can assess how severe the scarring has become by testing portal blood flow, as the portal vein goes directly to the liver.8 However, fibrosis tends not to cause symptoms, leaving many people undiagnosed until it has progressed too far, where they develop cirrhosis or liver failure.

Cirrhosis is the next stage of liver disease after fibrosis, when the liver is severely scarred and overtaken by fibrotic tissue.

If enough scar tissue develops, the liver completely loses function in those scarred areas, as liver cells are dead, the liver has shrunk and hardened, and blood flow is severely restricted.

While this is beneficial in small doses, persistent liver injuries and inflammation mean collagen is constantly deposited around liver cells. This nonstop “healing” causes excess collagen to continually harden around the normal liver tissue, which is how fibroids (or scar tissue) develop.8

This scar tissue can reduce or block blood flow within the liver, killing off healthy liver cells and perpetuating the cycle of collagen deposition to the injured sites. Cirrhosis is often characterized as compensated or decompensated. Compensated cirrhosis is a milder form in which the liver is still able to function despite the scarring, meaning the person probably won’t have symptoms.8

Decompensated cirrhosis is more serious, with people often appearing jaundiced or very sick. In this advanced stage, the abundance of scar tissue blocks blood flow through the portal vein.

As blood cannot flow into the liver, pressure increases and can cause portal hypertension (high blood pressure in the portal vein). This condition can lead to ascites (large amounts of fluid seeping out and pooling in the abdominal cavity, causing enlarged and hardened stomachs) or bleeding in the stomach, as the blood in the portal vein has nowhere else to go.8

While fibrosis is reversible up to a point, cirrhosis is not. There is also no treatment for cirrhosis, but if you stop drinking alcohol completely, it can significantly improve survival rates and prevent liver failure.9

Liver failure is an end-stage liver disease when the liver is damaged beyond repair. While cirrhosis is also a late stage of liver disease, some people’s livers are still able to function enough to survive.

The only treatment for liver failure is a liver transplant. Still, only about 10% of people with decompensated (advanced) cirrhosis from alcohol are referred for transplant each year—and only 1.2% actually undergo a liver transplant. This low rate is due to many reasons, one of which is that alcohol use disorder is often considered a “self-inflicted disease” with a high rate of potential relapse.10

However, as alcohol dependence is now understood to be a chronic neurological disease of addiction, rates of liver transplant for cirrhosis or liver failure may be increasing.

Lastly, hepatocellular carcinoma, a form of liver cancer, is another disease that can develop from excessive alcohol consumption.

People with decompensated liver cirrhosis have an increased risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma, with a lifetime risk of about 3% to 10%.5

Although there are other causes of this type of cancer, alcohol abuse has been found to increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma by 3- to 10-fold.11

Catching hepatocellular carcinoma early can lead to successful treatment with surgery or a liver transplant.

Fortunately, the liver is the organ most able to repair itself from alcohol-induced damage.

According to a review paper published in the journal Alcohol Research, “Even after years of heavy alcohol use, the liver has a remarkable regenerative capacity and, following alcohol removal, can recover a significant portion of its original mass and function.”5

However, not all forms of alcohol-related liver diseases can be reversed.

The first three stages—fatty liver, alcoholic hepatitis (or steatohepatitis), and fibrosis—can be reversed if the case is not too severe.

Alcoholic fatty liver disease (also known as hepatic steatosis) is the first stage of alcohol-related liver disease, and that is the easiest to turn around. Research shows that after just 2 to 3 weeks of alcohol abstinence, fatty liver completely resolves.5

Milder cases of alcoholic hepatitis (high levels of inflammation in the liver) and early stages of fibrosis (a buildup of scar tissue from the liver trying to repair itself after damage and inflammation) can also be reversed, but severe conditions of fibrosis cannot.12

Unfortunately, if you have progressed to cirrhosis—a late stage of liver disease where healthy liver tissue is replaced by scar tissue, and liver cells die or stop functioning—or liver failure, these stages are not reversible, even if you stop drinking. However, stopping drinking alcohol immediately can significantly increase survival rates in people with both early and late stages of cirrhosis or liver failure.9

A very important disclaimer: If you are dependent on alcohol or think you might have an alcohol use disorder, do not attempt to stop drinking alcohol on your own. It’s dangerous to quit alcohol cold turkey without medical supervision, as severe alcohol withdrawal symptoms can occur and be life-threatening. Please call the SAMHSA National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357) if you need help with mental health services, alcohol abuse, or substance abuse.

In bloodwork, the first signs of liver damage are elevated liver enzymes (ALT, AST, and/or GGT) in a liver function test. Your doctor can check these at your annual checkup. Symptom-wise, early signs of liver damage may include weakness, fatigue, pain in your liver region (upper right abdomen below the ribs), and nausea. Some people experience jaundice (a yellowing of the skin and eyes) in the early stages of liver disease.

Alcohol is a toxin that is harmful to the liver, the primary organ that metabolizes alcohol. However, what’s even more harmful to the liver is the intermediary byproducts that alcohol metabolism creates—namely acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde is a carcinogen that increases free radicals and oxidative stress, which damages liver cells and tissue. Over time, alcohol consumption also causes chronic inflammation, fat buildup in the liver, and fibrotic scar tissue buildup that replaces healthy and normal liver tissue.

Many stages of liver disease can be healed once someone stops drinking, including fatty liver and mild forms of alcoholic hepatitis and fibrosis. Fatty liver can heal within 2 to 3 weeks of alcohol cessation. However, advanced stages of liver disease, like severe fibrosis and cirrhosis, cannot be cured. That said, quitting drinking even in these later stages can improve survival rates.

The type of alcohol you drink does not matter to your liver when it comes to how it metabolizes it—it’s the amount and frequency with which you drink alcohol that can lead to liver damage, as seen with binge drinking and chronic heavy drinking. That said, alcohol mixed with sugar is probably harder on the liver than alcohol alone, as it has to process both compounds. Similarly, alcohol high in congeners (byproducts of distillation or fermentation processes), like whiskey, cognac, rum, and other dark liquors, may be harder on the liver because it must process those often toxic compounds.