Save $40 on your initial consult with a TNI Dietitian!

Talk to a real Dietitian for only $99: Schedule Now

This post contains links through which we may earn a small commission should you make a purchase from a brand. This in no way affects our ability to objectively critique the products and brands we review.

Evidence Based Research To fulfill our commitment to bringing our audience accurate and insightful content, our expert writers and medical reviewers rely on carefully curated research.

Read Our Editorial Policy

If you’re an avid coffee drinker, you probably roll out of bed, turn on your preferred coffee maker of choice, and down your first cup as soon as humanly possible.

However, recent health podcasters and social media trends have advised against this, recommending delaying caffeine intake from 60 to 120 minutes after waking.

While the reasoning behind this certainly sounds logical—it’s all about a chemical called adenosine, which we’ll get into—is there actually research to back up these claims?

In this article, we’ll look at all sides of the caffeine timing debate, including cortisol spikes, afternoon crashes, sleep quality, and more.

If you have heard about delaying caffeine in the morning for 60 to 120 minutes after waking up, you are probably one of Andrew Huberman’s 11 million-plus followers on Instagram and YouTube.

Dr. Huberman (the Ph.D. kind) is a neuroscience professor and researcher at Stanford who is undoubtedly intelligent and able to translate complex scientific data into actionable and accessible information—but he’s certainly not immune to backlash.

While I don’t necessarily think that someone’s private life has much to do with how they present health information to the world, more and more people are picking apart the quality of the evidence he shares in his podcast and social media—so much so that he’s been referred to as the “Goop for Bros.”

Huberman tangent aside, a leading tip in his much-followed health “protocols” is to delay coffee or caffeine ingestion in the morning for 60 to 120 minutes after waking.

The rationale behind this comes down to two molecules: adenosine and cortisol.

It’s thought that not having caffeine right away allows your morning cortisol to peak and fall in a more natural rhythm and allows adenosine levels to decline naturally.

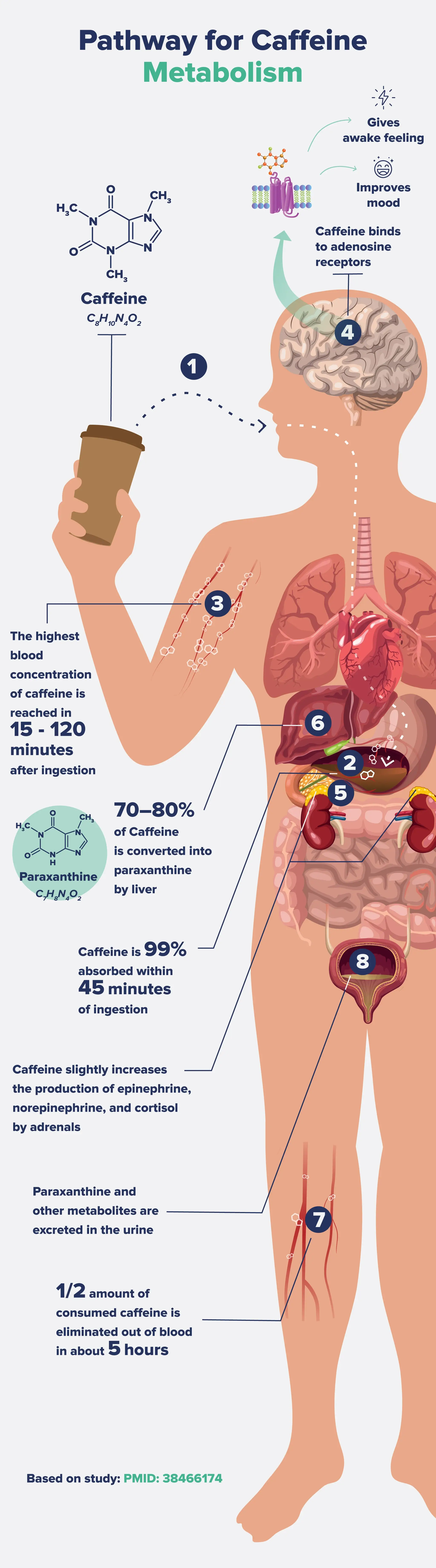

Adenosine is a neurotransmitter that builds up in your bloodstream and makes you tired later in the day or night. While you sleep, adenosine slowly dissipates.

Caffeine, as a chemical, has a very similar structure to adenosine. Therefore, when you guzzle your cup of joe, caffeine will bind to adenosine receptors instead of the sleep-inducing neurotransmitter, promoting that alertness we all know and love.

However, Huberman and others state that unbound adenosine doesn’t just disappear while you’re riding your caffeine high. After the caffeine wears off a few hours later, adenosine is still hanging around because it didn’t have a chance to dissipate naturally. It then binds to adenosine receptors in the brain and causes fatigue, drowsiness, and that dreaded afternoon crash.

Caffeine is also thought to increase cortisol levels. Cortisol is our primary stress hormone, and it has a natural peak first thing in the morning within the first hour or so of waking. This is beneficial for getting you up and ready for the day.

But drinking coffee first thing in the morning may also boost cortisol levels, which can spike cortisol too high, overtax your adrenal glands, or be less effective than drinking it later when your cortisol is naturally lower.

Well, that’s the theory, anyway. Let’s take a closer look at what the available evidence says.

According to a new paper published in The Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, “The validity and utility of these claims are questionable at best and, in some cases, not supported at all based on the available scientific evidence.”

Let’s first tackle the adenosine issue.

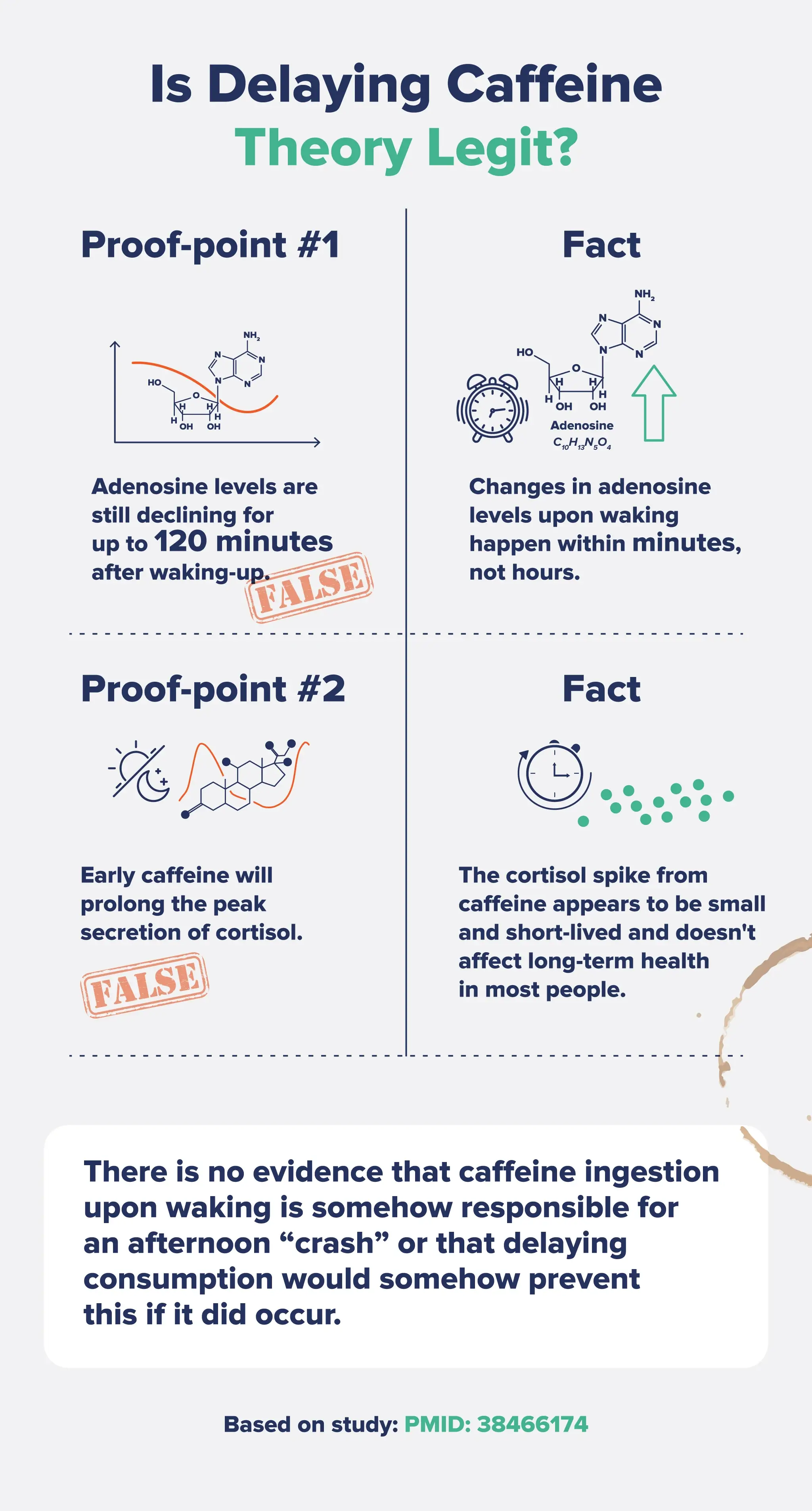

These researchers discuss adenosine metabolism in detail, citing data showing that changes in adenosine upon waking happen within minutes, not hours.

This means that we clear out adenosine more rapidly than the 60- to 120-minute timeframe referenced by Huberman and others. While it’s not disputed that caffeine binds to adenosine receptors to make you feel less tired, these researchers have an issue with the notion that delaying caffeine prevents an afternoon crash.

As they put it, “Any suggestion that adenosine levels are continuing to decline upon waking demonstrates a lack of understanding of the sleep-wake cycle influence on adenosine and would form a poor basis for recommending delayed caffeine intake for 90–120 minutes after waking.”

They also say, “If anything, delaying intake would simply push the need for an afternoon dose later, which could cause sleep disruption.”

The cortisol claims are much more nuanced, as cortisol production is influenced by factors other than caffeine, including other hormones, sex, genetics, activity levels, and more.

Overall, the cortisol-related rationale behind delaying caffeine intake is that morning coffee will prolong the peak secretion of cortisol, leading to excessive activation of the stress response and health problems like weight gain, metabolic dysfunction, and heart disease.

Research has shown that caffeine increases morning cortisol production—but only in people who haven’t been drinking it regularly.

After 5 days of not drinking caffeine, people in this study had elevated morning cortisol levels once they started drinking it again. But after just 5 days of being back on caffeine (at high doses of 300mg and 600mg/day), their morning cortisol responses were non-existent, suggesting our bodies get used to caffeine intake pretty quickly.

Plus, another study found that drinking coffee in more moderate doses (160mg) also did not affect salivary cortisol levels at all.

Overall, cortisol responses from coffee appear to be minimal and acute, likely not impacting long-term health.

Another flaw in this theory is that exercise in the morning also increases cortisol—so, with this logic, we’d also need to avoid morning exercise (which no one advises).

If there is a valid reason to delay caffeine intake, it has to do more with effectiveness than health outcomes. If you slept well the night before and feel well-rested, you probably do not need caffeine first thing in the morning—save it for later when you actually need it.

If you slept poorly or minimally, drinking caffeine first thing can obviously help to wake you up, as this is the scenario in which caffeine is the most effective for alleviating fatigue after sleep restriction.

As the cortisol response is highly individualized, people with cortisol irregularities (either too low or too high) might want to wait to delay caffeine intake—but this does not have solid evidence behind it, and most people do not know their daily cortisol patterns.

The cortisol confusion may partially be due to genetic differences in how we metabolize caffeine, which can make you a “fast” or “slow” metabolizer. (Slow metabolizers typically experience more of the negative side effects of caffeine intake, while fast metabolizers can have espresso after dessert with no insomnia-related consequences.)Overall, cortisol spikes after drinking coffee appear to be much lower among people who consume it regularly, and some studies show no rise in cortisol at all. Simply put, you probably do not need to delay caffeine intake based on potential cortisol spikes alone.

If you feel better by delaying your caffeine consumption for an hour or two after waking up, by all means, continue doing so.

But if those couple of hours of waiting are pure torture, counting down the minutes until you get your beloved cup of coffee, and you don’t feel much different after doing so, it’s probably not worth the struggle.

As new research is constantly being published that can contradict a previous study, almost nothing in health and nutrition research is black-and-white.

As of now, the most recent research says that delaying morning caffeine intake might be beneficial in people who slept well (as they don’t need the energy boost right away) and in those with cortisol irregularities—but this still is not confirmed.

Similarly, if you feel jittery, anxious, or experience other negative side effects from caffeine, it might be worthwhile to eat a protein-rich breakfast before your morning cup, limit your overall caffeine intake, and consider delaying it an hour or two. This is not to minimize an afternoon crash, but simply to feel better.

You could also give a mushroom coffee brand like Four Sigmatic a try, which is said to reduce the “crash” and jitters that often come with coffee.

Last, but not least, it’s worth examining what you’re putting in your coffee—meaning it may not be the coffee that causes adverse effects, but rather, the dozens of grams of sugar and sweet creamers.

Antonio, J., Newmire, D. E., Stout, J. R., et al. (2024). Common questions and misconceptions about caffeine supplementation: what does the scientific evidence really show?. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 21(1), 2323919. https://doi.org/10.1080/15502783.2024.2323919

Lovallo WR, Whitsett TL, al’Absi M, Sung BH, Vincent AS, Wilson MF. Caffeine stimulation of cortisol secretion across the waking hours in relation to caffeine intake levels. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(5):734-739. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000181270.20036.06

Papakonstantinou, E., Kechribari, I., Sotirakoglou, Κ., Tarantilis, P., Gourdomichali, T., Michas, G., Kravvariti, V., Voumvourakis, K., & Zampelas, A. (2016). Acute effects of coffee consumption on self-reported gastrointestinal symptoms, blood pressure and stress indices in healthy individuals. Nutrition journal, 15, 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-016-0146-0

Reichert, C. F., Deboer, T., & Landolt, H. P. (2022). Adenosine, caffeine, and sleep-wake regulation: state of the science and perspectives. Journal of sleep research, 31(4), e13597. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13597