This post contains links through which we may earn a small commission should you make a purchase from a brand. This in no way affects our ability to objectively critique the products and brands we review.

How Does Alcohol Affect the Heart?

Evidence Based Research To fulfill our commitment to bringing our audience accurate and insightful content, our expert writers and medical reviewers rely on carefully curated research.

Read Our Editorial Policy

Although the liver is the organ most commonly associated with alcohol consumption, your heart and cardiovascular system can also be significantly affected.

With heart disease remaining the number one cause of death in the United States, it’s time to take a look at how alcohol plays a role in cardiovascular health.

Despite mainstream media over the past couple of decades repeating the claim that light alcohol consumption (especially red wine) is good for heart health, recent research has disproved this over and over again.

In this article, we’ll go over how alcohol impacts various aspects of the cardiovascular system, plus some reassuring information about reversing heart damage from alcohol consumption.

A very important disclaimer: If you are dependent on alcohol or think you might have an alcohol use disorder, do not attempt to stop drinking alcohol on your own. It’s dangerous to quit alcohol cold turkey without medical supervision, as severe alcohol withdrawal symptoms can occur and be life-threatening. Please call the SAMHSA National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357) if you need help with mental health services, alcohol abuse, or substance abuse.

Effects of Alcohol on the Heart

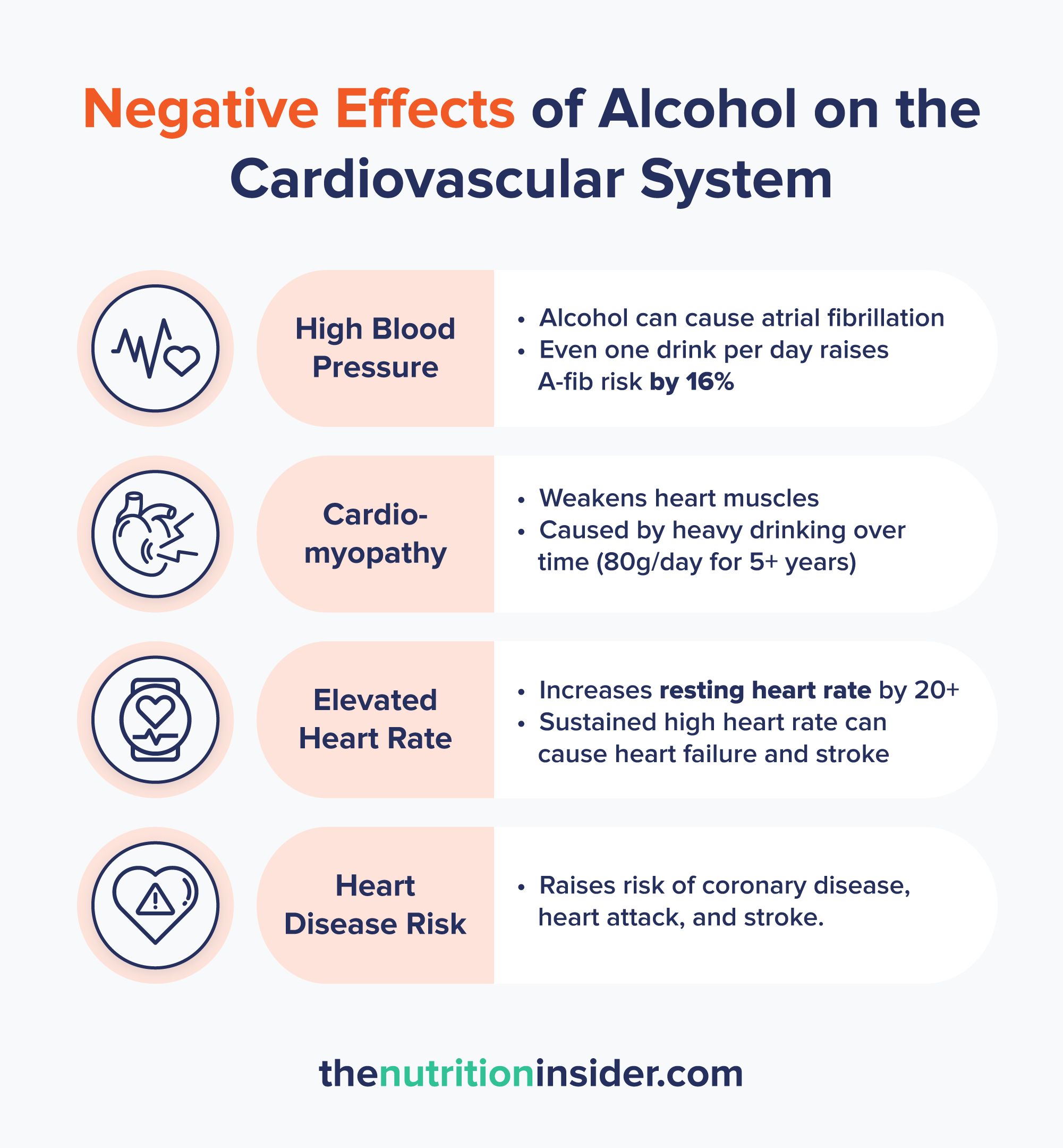

Chronic or heavy alcohol consumption can impact many areas of the cardiovascular system, including high blood pressure, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, elevated heart rate, and an increased risk of heart disease, heart attack, and stroke.

Alcohol and Blood Pressure

Alcohol can increase your blood pressure, which is one of the leading causes of heart disease, heart attacks, and stroke.1

It’s thought that alcohol consumption is responsible for 16% of hypertensive disease cases worldwide—a substantial amount.2

High blood pressure or hypertension occurs because alcohol disrupts your sympathetic nervous system—the one controlling the constriction and dilation of blood vessels—causing your blood vessels to narrow and increasing the pressure of the blood flow inside them.

Research shows that blood pressure increases by approximately 1 mmHg for every 10 grams of alcohol consumed (about one standard drink).2

As a quick aside, alcohol can also cause the opposite effect on blood flow in the short term, known as vasodilation (the relaxation of blood vessels).

Alcohol and Arrhythmias

Alcohol can also cause palpitations and arrhythmia (an uneven and irregular heartbeat), which can increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

It’s so well-known that alcohol leads to irregular heartbeats that the term “holiday heart syndrome” was coined. After the booze-filled holidays, doctors see an uptick in cardiac arrhythmias like atrial fibrillation.3

Atrial fibrillation (“A-fib”) is the most common type of heart arrhythmia, characterized by an irregular rhythm in the upper chambers of the heart, feeling like fluttering or rapid pounding sensations in the chest.

A single session of binge drinking can cause heart rhythm changes, and so can drinking too much over time. Research shows that even a single drink per day is linked to a 16% higher risk of developing A-fib compared to those who didn’t drink.4

Elevated heart rate also occurs from alcohol consumption—both acutely and chronically. Many people who wear smartwatches find that a night of heavier drinking can increase their resting heart rate by 20 bpm (beats per minute) or more.

Alcohol also increases cortisol—our body’s primary stress hormone—and activates the “fight or flight” response, which is known to increase heart rate.5

A resting heart rate of over 100 bpm (which can happen from drinking alcohol) is called tachycardia. Having many episodes of tachycardia can lead to more severe issues like heart failure or arrhythmias, increasing the risk of heart attack and stroke.6

It’s not just the act of drinking that elevates heart rate—the withdrawal period (aka a hangover) also increases it. Studies show that healthy people without alcohol use disorder have a 17% increase in resting heart rate 12 hours post-binge.3

Alcohol and Heart Disease

Habitual alcohol consumption raises the risk of coronary artery disease, the most common form of heart disease and the leading cause of death in the United States.7

In a study of over 371,000 adults in the UK, alcohol consumption of all amounts was associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease, heart attack, stroke, heart failure, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation.7

Light or moderate alcohol intake (within guidelines) only minimally increased the risk, while several-fold increases in risk were found for people having 21 or more drinks per week.

The researchers determined that any benefit of light-to-moderate drinking to heart health (as is commonly stated in news outlets) is due to other healthy lifestyle factors. For example, people who follow health guidelines for alcohol (1 drink per day for women and 2 for men) are also more likely to follow nutrition and physical activity guidelines, which confounds the results.7

Several markers are also correlated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease, including high triglycerides, LDL and VLDL cholesterol, and increased heart rate, all of which can be heightened by alcohol consumption.7

Alcohol and Cardiomyopathy

Alcohol weakens the heart muscles—a condition known as alcohol-related cardiomyopathy or alcoholic cardiomyopathy—which reduces the heart’s ability to pump blood effectively throughout the body. Over time, this can lead to heart failure.

Cardiomyopathy develops because repeated exposure to ethanol or its metabolites (like the super-toxic acetaldehyde) causes oxidative stress, cellular injury, and mitochondrial dysfunction within the heart muscles. This causes myocyte (heart muscle cell) death, weakening the heart’s overall ability to pump blood.

According to research from 2024, the amount of alcohol required to develop alcohol-induced cardiomyopathy is generally considered as >80 g/day over five years, which is about eight drinks or more per day.8

However, that’s not always the case, and some people with genetic predispositions are more susceptible to developing it at lower intake levels.

Can You Reverse Alcohol Damage to the Heart?

Some of these symptoms, including palpitations, arrhythmias, and elevated blood pressure, can begin to normalize within days of quitting drinking.

One study had healthy drinkers abstain from alcohol for one month. Compared to a control group that continued drinking, the abstainers saw significant reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, body weight, and insulin resistance.9

In just one month of not drinking, blood pressure was reduced from an average of 136/89 mmHg to 125/82 mmHg. While that may not seem like a huge difference, it is pretty remarkable for one month. Plus, research has shown that even a 5 mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure (the top number) drops cardiovascular disease risk by 10%.10

Another study found that people with alcohol use disorder and cardiomyopathy who abstained from alcohol completely had significantly increased left ventricular function, indicating how well the heart pumps blood.11

Unhealthy levels of cholesterol and triglycerides can also revert to normal numbers pretty rapidly, with many people seeing significant changes within one month of quitting alcohol.

When it comes to cardiomyopathy, complete alcohol abstinence is needed to reverse the damage. People who continue drinking have worse outcomes and increased mortality rates than those who quit.8

Case studies have shown that alcohol abstinence allows for the reversal of alcohol-related cardiomyopathy.12

However, if the damage is severe and heart failure has occurred, the chances of full recovery are lower, and you likely won’t even be entirely cured of the condition.

Overall, the good news is that you can reverse much of the damage done to the heart if you stop drinking.

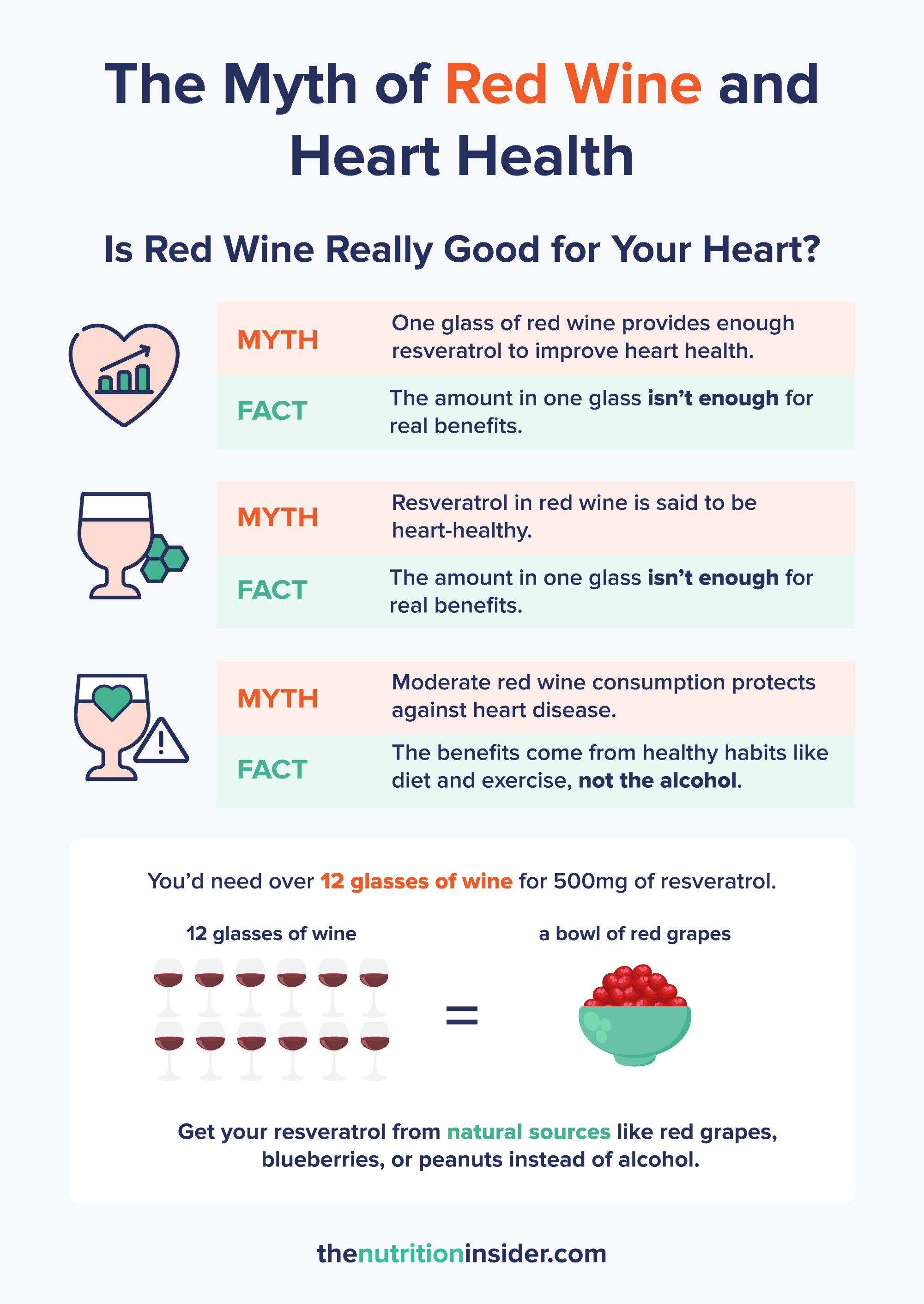

But Isn’t Red Wine Good for Your Heart?

The link between red wine and heart health has been seriously overhyped in years past, leading many people to believe their nightly glass (or two) of Cab was improving their heart health. This theory came from research showing that the antioxidant resveratrol—found in red grapes and wine—improves cardiovascular health, among other things.13

While red wine does contain resveratrol, you’d have to drink immense amounts to get clinically relevant benefits. To get 500mg of resveratrol (a standard supplemental dose), you would need to drink over 12 glasses of red wine.

Twelve glasses of wine daily will cause detrimental health effects that a bit of resveratrol can’t fix. We now also know that any amount of alcohol is harmful to heart health, regardless of the minuscule amounts of resveratrol it may contain.

If you want to get some resveratrol without the harmful effects of alcohol, opt for a glass of non-alcoholic red wine—or simply snack on some red grapes!

While some observational studies have shown that moderate wine consumption (1 to 4 glasses per week) is linked to fewer cardiovascular events, other factors are probably at play.14

According to researchers published in The American Journal of Medicine, “Although moderate wine consumption is probably associated with low cardiovascular disease events, there are many confounding factors, in particular, lifestyle, genetic, and socioeconomic associations with wine drinking, which likely explain much of the association with wine and reduced cardiovascular disease events.”15

Alcohol and Heart Health FAQs

Is it normal to have heart palpitations after drinking alcohol?

It is common—but not normal—to have heart palpitations after drinking alcohol. Alcohol can trigger irregular heartbeats and arrhythmias (like atrial fibrillation) and elevate heart rate because it causes a stress response and disrupts normal electrolyte balance and electrical activity.

Will A-Fib go away if I stop drinking?

If you have atrial fibrillation related to alcohol consumption, stopping drinking can resolve it. However, not all A-fib is from alcohol use. That said, eliminating alcohol can help to reduce the recurrence of it.16

What is alcoholic cardiomyopathy?

Alcohol-induced cardiomyopathy is the weakening of the heart muscles in response to chronic and heavy alcohol consumption (typically eight drinks or more per day for five years). Cardiomyopathy develops because repeated exposure to ethanol or its metabolites (like the super-toxic acetaldehyde) causes oxidative stress, cellular injury, and mitochondrial dysfunction within the heart muscles. This causes myocyte (heart muscle cell) death, weakening the heart’s overall ability to pump blood, which can lead to heart failure if untreated.

Is heart damage from alcohol reversible?

Yes, most heart damage from alcohol is reversible—as long as the damage is not too severe. Conditions like hypertension, arrhythmias, high cholesterol, and even cardiomyopathy have all been found to resolve or significantly reduce after quitting drinking alcohol.

- Husain, K., Ansari, R. A., & Ferder, L. (2014). Alcohol-induced hypertension: Mechanism and prevention. World journal of cardiology, 6(5), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v6.i5.245

- Puddey, I. B., & Beilin, L. J. (2006). Alcohol is bad for blood pressure. Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology, 33(9), 847–852. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04452.x

- Jain A, Yelamanchili VS, Brown KN, et al. Holiday Heart Syndrome. [Updated 2024 Jan 16]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537185/

- Csengeri, D., Sprünker, N. A., Di Castelnuovo, A., Niiranen, T., Vishram-Nielsen, J. K., Costanzo, S., Söderberg, S., Jensen, S. M., Vartiainen, E., Donati, M. B., Magnussen, C., Camen, S., Gianfagna, F., Løchen, M. L., Kee, F., Kontto, J., Mathiesen, E. B., Koenig, W., Stefan, B., de Gaetano, G., … Schnabel, R. B. (2021). Alcohol consumption, cardiac biomarkers, and risk of atrial fibrillation and adverse outcomes. European Heart Journal, 42(12), 1170–1177. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa953

- Yang, J. H., Kweon, S. S., Lee, Y. H., Choi, S. W., Ryu, S. Y., Nam, H. S., Park, K. S., Kim, H. Y., & Shin, M. H. (2021). Association between Alcohol Consumption and Serum Cortisol Levels: a Mendelian Randomization Study. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 36(30), e195. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e195

- Palatini, P., & Julius, S. (2004). Elevated heart rate: a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Clinical and experimental hypertension (New York, N.Y.: 1993), 26(7-8), 637–644. https://doi.org/10.1081/ceh-200031959

- Biddinger, K. J., Emdin, C. A., Haas, M. E., Wang, M., Hindy, G., Ellinor, P. T., Kathiresan, S., Khera, A. V., & Aragam, K. G. (2022). Association of Habitual Alcohol Intake With Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Network Open, 5(3), e223849. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.3849

- Domínguez, F., Adler, E., & García-Pavía, P. (2024). Alcohol cardiomyopathy: an update. European Heart Journal, 45(26), 2294–2305. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae362

- Mehta, G., Macdonald, S., Cronberg, A., Rosselli, M., Khera-Butler, T., Sumpter, C., Al-Khatib, S., Jain, A., Maurice, J., Charalambous, C., Gander, A., Ju, C., Hakan, T., Sherwood, R., Nair, D., Jalan, R., & Moore, K. P. (2018). Short-term abstinence from alcohol and changes in cardiovascular risk factors, liver function tests, and cancer-related growth factors: a prospective observational study. BMJ open, 8(5), e020673. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020673

- Jones, L. (2021). Lowering blood pressure is even more beneficial than previously thought. British Heart Foundation. https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/news-from-the-bhf/news-archive/2021/april/lowering-blood-pressure-is-even-more-beneficial-than-previously-thought

- Nicolás, J. M., Fernández-Solà, J., Estruch, R., Paré, J. C., Sacanella, E., Urbano-Márquez, A., & Rubin, E. (2002). The effect of controlled drinking in alcohol- cardiomyopathy. Annals of Internal Medicine, 136(3), 192–200. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00007

- Baudet, M., Rigaud, M., Rocha, P., Bardet, J., & Bourdarias, J. P. (1979). Reversibility of alcoholic cardiomyopathy with abstention from alcohol. Cardiology, 64(5), 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1159/000170629

- Gal, R., Deres, L., Toth, K., Halmosi, R., & Habon, T. (2021). The Effect of Resveratrol on the Cardiovascular System from Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Results. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(18), 10152. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221810152

- Goldwater, D., Karlamangla, A., Merkin, S. S., & Seeman, T. (2019). Compared to non-drinkers, individuals who drink alcohol have a more favorable multisystem physiologic risk score as measured by allostatic load. PloS one, 14(9), e0223168. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223168

- Krittanawong, C., Isath, A., Rosenson, R. S., Khawaja, M., Wang, Z., Fogg, S. E., Virani, S. S., Qi, L., Cao, Y., Long, M. T., Tangney, C. C., & Lavie, C. J. (2022). Alcohol Consumption and Cardiovascular Health. The American journal of medicine, 135(10), 1213–1230.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.04.021

- Thiel, D. J., Marshall, R. C., & Rogers, T. S. (2022). Alcohol abstinence reduces A-fib burden in drinkers. The Journal of Family Practice, 71(2), 85–87. https://doi.org/10.12788/jfp.0363